Tom Young

Our Time On Earth

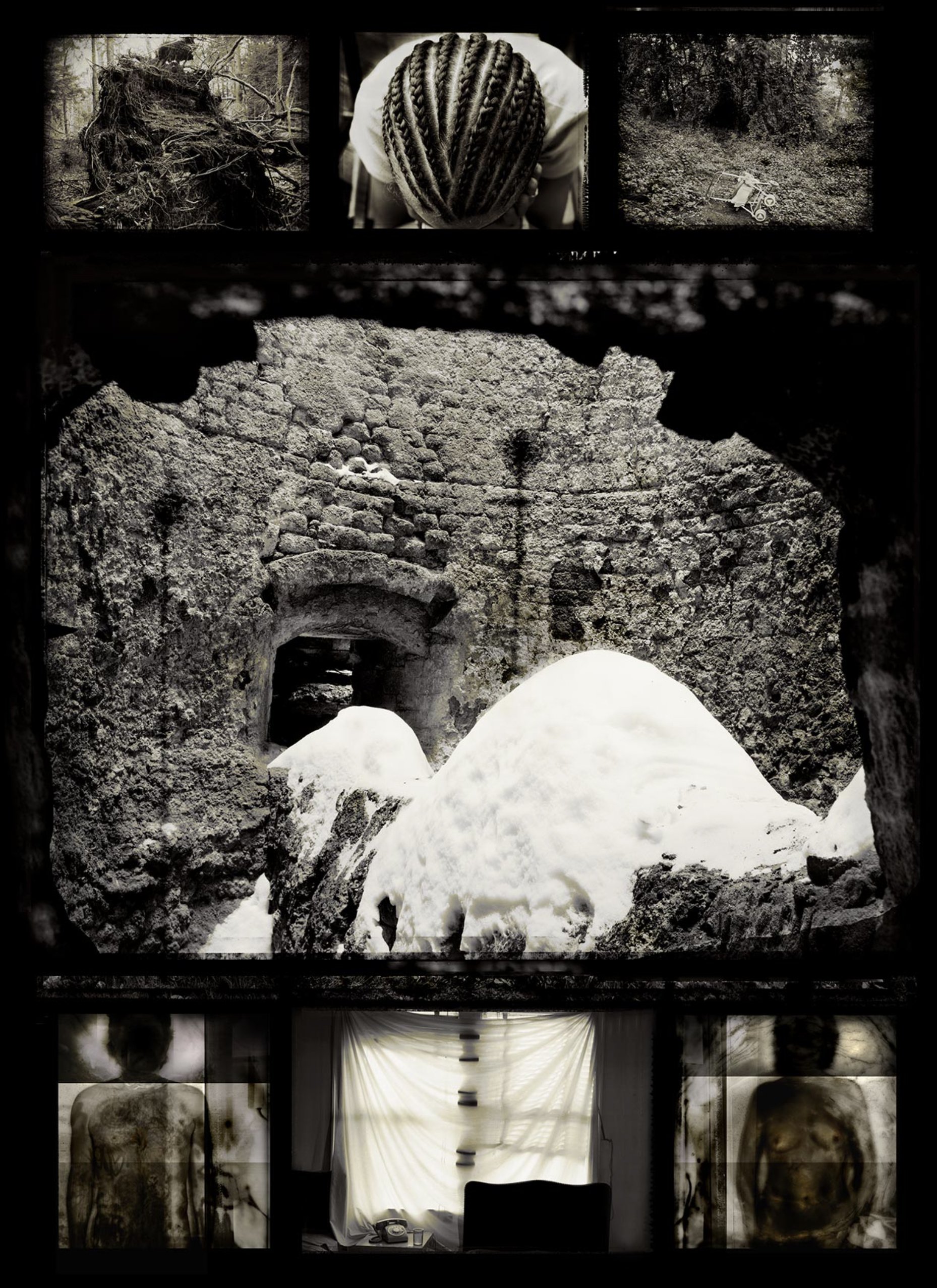

Tom Young, Worship, From the portfolio Our Time On Earth, 2020, Inkjet print, 36 x 24 inches, Gift to MMPA from the Bill Press Collection

We have the world to live in on the condition that we

will take good care of it. And to take good care of it,

we have to know it. And to know it and to be willing

to take care of it, we have to love it.

—Wendell Berry, from an interview on

Moyers & Company (October 4, 2013)

We at MMPA are so honored to receive a gift of twenty prints made by the gifted photographer, Tom Young. From the portfolios of Timeline: Learning to See with My Eyes Closed (George F. Thompson, 2012), and Our Time on Earth (George F. Thompson, 2020), the photographs span ten years and show the beautiful evolution of Tom’s vision. Three generous donors, Bill Press, Harry Brandler and Ralph Segall made this possible. The selection of images below is from the portfolio, Our Time On Earth.

“Artist/photographer Tom Young has a stated interest in what he calls reverb—the traces we leave behind and what they say about us. I could say “the traces humans leave behind,” but Young is more deliberate in his “we,” for there is a sense of belonging and responsibility that goes along with human impact, in which each person is individually implicated. His newest project grew organically: He sought out places where the visual residue of human agency were visible to him both in places where we might think they exist (such as degraded industrial sites he is so fond of photographing) and places where it might not occur to us to look.

Many of the images evoke these layers of awareness through juxtapositions of visual barriers—mirrors, plastic, water, mist. Each is a framed window that both blocks and invites peering… The aggregate of viewing is an awareness of the deep interconnectedness of humans and their environment, a drama that plays out in equally beneficial and devastating ways.

— Aprile Gallant,

Senior Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs at the Smith College Museum of Art

Timeline: Learning to See with My Eyes Closed

Tom Young, Taking Flight, From the portfolio, Timeline: Learning to See with My Eyes Closed, 2009, Inkjet print, 44 x 32 inches,

Gift to MMPA from the Ralph Segall Collection

Time, memory and mystery are paramount in the work that I do. I seek out places to photograph where I feel something of import has happened and that memory seems to linger and present itself to me. Most photographs are about location, where we are in the world. I think my photographs are more about dislocation, where place becomes fused with memory and imagined history.

— Tom Young

For some of us,

the big question is,

Why are we here?

I have never gotten

past thinking about

what here is.

— Gregory Conniff

Seeing Through Time

How does one see with their eyes closed? For many photographers, it is a life-long quest to make a photograph feel like the experience of a scene rather than just make a visual representation of it. Tom Young learned this at the early age of 10 years old through the difficult experience of a sightless world for several weeks after eye surgery. While his eyes were healing under the bandages, Tom’s other senses developed into a heightened state of awareness which stayed with him for life. When the bandages were removed from his eyes, the intensity of daylight was quite painful and Tom had to reacclimate his visual senses to the world. Photography became his chosen medium of expression while studying at Goddard College, as his vision had a similar affinity to light as film, and by making images that felt like brief moments of memory or dream that became a direct representation of how his mind experienced the world. In the book, Timeline: Learning to See with My Eyes Closed, Tom created a visual narrative of the personal experiences of family life intertwined with the landscape. Working with a large format camera, blocking out distractions, the world unfolded on the ground glass as if in a dream. Combining images of ephemeral family moments with landscapes that hold the weight of history, a story develops through the conversation between the individual images. In 2016 Tom published, a second book with George F. Thompson Publishing, Backscatter: Between Here and There. This series was an exploration in the quality of backscatter, or particles that reflect or refract light as seen through the lens. Photographing at times just below the sea surface and at others through mist suspended in the air, Tom brings the viewer to an elemental experience of Earth’s most essential compound: H2O. Water, reflecting or refracting light, or raining down on humans passing through the mist, envelops the images with the wonder of its life-giving properties. Tom continues this thought of human impact on the environment in his latest book, Our Time on Earth. It is a poetic, emotional response to the state of the environment in this age of the Anthropocene. Yes, some images that contribute to the scene seem apocalyptic, but throughout the series there is also a thread of hope that nature is resilient and adaptable enough that it will go on, possibly even without us.

Curious about Tom’s vision, I enjoyed a wonderful conversation with him about the depth of experience behind the images. I hope the following interview may shed some light on how we can see the world with our eyes closed and our heart open.

— Deb Dawson

Tom: I've always been interested in how images can be joined together to create language. When photographs are juxtaposed with one another, whether it’s on a gallery wall, in a book, or through collage, new meanings arise that are beyond the individual images themselves. It’s the space between them that develops, a new language. This is less about each of the pictures and more about the invention of a new literature.

Deb: In the introduction of Timeline: Learning to See with My Eyes Closed, you describe a childhood experience of being without sight for several weeks after a medical procedure. That must have been incredibly scary for a 10 year-old to endure. Yet, looking back, you can remember how your senses changed and you could imagine the world around you like a memory. How did this early experience affect your experience of the world when you regained your sight?

Tom: As described in the book, Timeline, at ten I had surgery on my eyes. After weeks of bandaged eyes the doctor took off the bandages, and the light hitting my eyes was one of the most painful experiences in my life. I remember shutting my eyes tightly and said to my mother, I never want to open my eyes again. That statement was short lived as I struggled to see again. My eyes were very sensitive to the light for a long time afterwards and I had to wear dark glasses. I don't have that problem anymore, but it elicited a response in me about the power of light, about light being both painful and revealing. So has it affected my life—Absolutely it has. During high school, I became interested in vision and blindness and worked at the Perkins School for the blind teaching swimming which further interested me in the physical and psychological nature of sight and blindness.

At the age of 39, I was diagnosed with a life threatening illness and I was not supposed to live very long. As it turns out, I was one of lucky ones who seems to have survived. It has given me an altered sense of time. Time, memory and mystery are paramount in the work that I do. I seek out places to photograph where I feel something of import has happened and that memory seems to linger and present itself to me. Most photographs are about location, where we are in the world. I think my photographs are more about dislocation, where place becomes fused with memory and imagined history.

Deb: I think there are some universal truths that you help us to realize through your photographs. It's really fascinating how our memories work with our experiences. I think we have like a visual catalog in our minds and they're just little glimpses of the past. Going through your series of photographs, I feel like I'm kind of working through this whole catalog of dreams, experiences and meaning.

Tom: I think your read is on track with something that I tend to also feel. Photographs can elicit a response of both understanding of what’s in front of us and taking us somewhere else. I'm always surprised that people seem to get it or at least understand the tenor of the story. Maybe, not a literalness, which I'm not that interested in, but an emotional response that is tied into who we are and our history.

Deb: Can you describe your introduction to photography?

Tom: When I was in college studying the fine arts, over Christmas vacation I went home to my parents’ house to visit and photograph. Like many of us, I had a childhood filled with all kinds of dysfunction and tension in the house. I photographed both my parents and the light and shadow in the the house. When I got back to school, I put the printed photographs up in a critique, people talked about how they looked scary in some ways—how they had this sort of embrace of love but at the same time, there was terror. The discussion gave me confidence that I could photograph in a way that felt true and could trust that language would be developed.

At this stage in my process, I was wonderfully surprised that the act of making photographs could elicit language not just from me, but from the viewers as well. I realized a new kind of communication for me. I've always been interested in the photograph as language and I was a very shy kid growing up—I barely spoke. Then I found art making as a way to speak and I think that somehow it gave me some kind of strength to then use my verbal voice. So making photographs became both a way of coping and a charge in my life.

When attending RISD, I moved to Providence from very rural part of Massachusetts. This city environment was a very unfamiliar place to me. I remember going to talk to one of my professors, Harry Callahan on the first week of school. I told him that everything seems so different, I just didn’t know what to make photographs about. Harry said, “Tom, all that you can do is respond with what you feel. Look around in the world and be aware of what is drawing you to it and that must have some import and to trust it.” He then went on to say, “If you're not making art about who you are, then you're just playing the art game and you're going to be just another number.” That advice, about being true to something you feel, gave me permission to follow what was important to me. I think most young art makers struggle with trusting themselves as they produce work. Although I've had some unlucky experiences in life, I do feel that I am so very fortunate to have this ability to make art that it true to what I’m deeply concerned about and believe in following that passion, hoping that it fits into some part of the world.

Deb: Much of your recent work is in the form of juxtaposing photographs into collages that transform different scenes into a beautifully composed story drawing the viewer in to experience from their own familiar vantage point. I’m thinking of the photograph, “When I Close My Eyes” where there are scenes that feel like universal memories from childhood—just those brief glimpses of life that we may remember as a dream. Can you describe how these images come together for you in your process?

Tom: That’s a wonderfully mysterious process to me. I usually begin with a new photograph I have made that suggests a kind of non-literal narrative. I then mine through many years of images to find photographs that visually come together with others in order to form something new in terms of content. I feel like I'm excavating past work and putting it into a new context, which for me connects the past to the present. So, a photograph made 30 years ago can be connected with something I made yesterday. It's just fascinating to me if there is a link that I see, feel and experience. Because sometimes I put photographs together and they visually are kind of dynamic, but for me, empty of the kind of content that I'm looking for. So I tend to wait to put things out until I really understand what I want from them and therefore what other people might have access to. They seem to speak about something else. Metaphor is maybe more interesting to me than the physicality of the world.

Deb: A lot of your single images are pretty abstract, but when you marry them with another image, that is of completely different subject matter, a connection develops between them creating a metaphorical context. I'm looking at the image entitled “Worship” right now. The lower portion is the back of a goat and the upper portion is a collapsed fuel tank. Two very different subjects that at first seem completely unrelated, but there's a connection between them.

Tom: Yes. There’s a visual connection between the arc of the top of the goat and the arc of the fuel tank that I think it makes it work together formally. Then one starts to think about the linkage in terms of content. I think it's mysterious and I do think the most exciting things in life are about mystery.

There’s something fundamental about seeing the mysteries of the world. I’ve been working on a new series of pictures that seem to have come out of another traumatic experience. I had a pretty bad head concussion six months ago and it knocked floaters in my eyes. For weeks I was looking at the world with these floaters in my vision and it seemed like they were also in my photographs. That experience, I think has somehow led in a strange way to the pictures I’m making now. So it always comes from something I feel deeply about which I guess is true with all of us. Influenced by these powerful experiences, I can continually explore the mysteries of life, linking together past and present through photographs.

George F. Thompson Publishing just put together three of my books, Timeline, Backscatter and Our Time on Earth as a kind of trilogy. George wrote about the linkages of time and I thought he expressed that better than I could have…

“In Tom Young's trilogy of books, the common thread is time: the marking of time in one's personal life and the events that unfold, the marking of time in society in which one can see change on the landscape and in our towns, homes, and cities, the marking of time on our planet Earth, in which we see the impact of human life on our planetary home. With this trilogy, Tom Young has made a lasting impression in the world of photography and art in how he renders time in our collective and individual lives.”

—George F. Thompson

Deb: What about the technical aspect of creating your photographs? How does the camera and process influence your vision?

Tom: For most of my life I've worked with a view camera under a dark cloth, which I don't anymore because of this digital world. But that was a really important formative experience because when you go under the black cloth to compose a photograph, the 4x5 illuminated screen becomes your entire world, and everything else is black. That experience of blocking out everything in the world and looking at the image on this glowing piece of glass, I think is partly what kept me so interested in this medium. But it's now in the past; Very few of us are making photographs like that now, although there has been some renewed interest. I used to go out and make six pictures with the 4x5. Now I make sixty with my medium format digital camera. It's a dramatic shift in the way of working through the process.

Deb: So has the process of transitioning from the world of working with a view camera to now photographing with digital cameras changed your vision?

Tom: I think it has. You know in analog photography, you never really knew what was going to happen. It's a wonderfully recalcitrant process that’s filled with surprises. And now with digital, it does exactly what I think it's going to do. It's totally controllable. So, it forces me to take other kinds of chances with what I do. When I was shooting film, I was fortunate enough to be sponsored by the Polaroid Corporation. So I was shooting 4x5 Polaroid film which was wonderful because it it's pretty unstable in terms of the batch and temperature conditions. Sometimes it would solarize or the emulsion would lift off… I loved that. Timeline was shot on Polaroid film, where you see some of the distressed portions and film edges. It was, it was wonderful. Although, the film base is really Panatomic-X, which is super contrasty—has a very short scale. It cannot handle a lot contrast unless you pre-expose it and fog it, so I was always shooting late in the afternoon or early morning with long exposures. What I realized is the film, like my eyes as a kid after surgery didn't like bright light. So we had sort of an agreement.

Deb: The theme of our place in the environment also seems to run through many of your photographs even before the book, Our Time on Earth. Are there particular experiences that stand out in your life that drove you to look to the land for inspiration and expression?

Tom: I am critically concerned about the environmental issues we face. I've always been involved in environmental issues since I was a high school student. In high school I also worked as an intern helping to put together environmental slide talks for kids at the Massachusetts Audubon Society. I was always interested in exploring this place we call home in the small sense and in the larger scale. It was Einstein who said that art and science are closely related in that they are about exploring the mysterious. And I just think that says it all.

Place is important to me. Most images photographers make are about location. But I think my pictures are more about dislocation. I think when we look at the photograph, it's not that we think so much about where we are, but rather that they evoke a feeling through metaphor, or through another kind of suggestion that moves you away from place and more into some other kind of content. I think that's true with the Our Time on Earth photographs—that idea of dislocation which is important. In the Our Time on Earth series there was a switch in perspective for me. I like to think of John Szarkowski’s book, Mirrors, and Windows, where he divided contemporary photography (at that time) into two different groups, mirror and window, which a lot of people challenged and I did too. The premise was that all photography could be divided into two groups such as Minor White's idea of the mirror or Robert Frank's idea of the window. Our time on Earth is as close as I've come to creating pictures that are about the window. They are about looking out into the world. Yes, there's always mirror in my pictures, but I was really trying to look around and think about what we're doing to this planet—how we're leaving it for this next generation, which is much more intellectual than emotional, but the emotional part is just built in for me. This was a change in perspective from the Timeline series, where those photographs were all about the mirror. Looking inward, Timeline was about illness and family and struggle and finding beauty in something that many of us might read as the horrific. This way of finding beauty in the midst of decay seems to be a common thread throughout my work, whether the photographs are made from within or looking out into the world.

Deb: Some of your images portray some apocalyptic scenes of decay, yet they’re infused with a thread of hope that nature will carry on with or without us. Is this dichotomy at play in your mind as you seek out these photographs? Or does it come together through the process of composing the collages?

Tom: There is some hope in there—about nature taking back over after we've left this mess. I think that the treatment of what I'm looking at is so infused with visions of form and beauty, of finding hope in the darkness, that maybe the photographs can also give the viewer some hope. I feel very hopeful even though it’s very scary what's going on in the world right now. We are hit with so many facts about what we're doing wrong. The science is truly important, and there are many great photographers making images that document the threat. But my thought in creating the Our Time On Earth photographs was can I make a book about the environment that is emotional? I wanted to make a book that isn't directly pointing to only our scientific knowledge, but rather talks about it in a more poetic way of emotional response. I’d rather give someone bits of information that are strung together with some clarity that ask the viewer to go in and come to an understanding themselves, of what this all means—to find their own emotional response to what’s happening in the world and act on it.

Biography:

Tom Young was born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1951. He received his B.A. in photography from Goddard College in 1973 and his M.F.A. in photography from the Rhode Island School of Design in 1977. He is Professor Emeritus at Greenfield Community College. Since leaving full-time teaching, he has been a visiting artist at Amherst College, Hampshire College, the University of North Dakota and Greenfield Community College. He has received an Artist Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, five Artist Fellowships from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, and, in 2009 the Governor’s Citation for contributions to the arts in Massachusetts. Tom’s photographs are included in more than thirty permanent collections, including the Amon Carter Museum, Bibliotheque Nationale de France, Center for Creative Photography, George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film, High Museum of Art, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and Yale University Art Gallery. Young’s photographs have also appeared in more than eighty exhibitions worldwide, including those at the International Center of Photography, Frans Hals Museum, Kunsthalle, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Caracas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, and Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography. His previous books of photographs are Backscatter: Between Here and There (George F. Thompson, 2016), Timeline: Learning to See with My Eyes Closed (George F. Thompson, 2012), and Recycled Realities, with John Willis (Center for American Places, 2006). His photographs have also appeared in American Perspectives (Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, 2000), Goodbye to Apple Pie (deCordova Museum, 1992 and Artworks: Tom Young (Williams College Museum of Art, 1990). He resides in Buckland, Massachusetts, with his wife, and daughter. His website is www.tomyoungphoto.com