Dawn Surratt, Ephemerality, 2022, Mixed media, 62 x 93 inches, $8,500.

Dawn Surratt’s Ephemerality

by Deb Dawson

As the assigned family archivist, I have amassed a personal collection of twentieth century domestic photographs. What do these piles of mementos from parents, grandparents and great grandparents hold? And why is it so difficult to let them go? As time slips through my fingers, my hands grasp at the bits and pieces of memories contained in those boxes of family photographs and letters.

Our featured artist Dawn Surratt understands this dilemma and expresses emotions of loss and memory through her installations consisting of dreamlike photographic prints combined with antique objects. Her understanding of the ephemerality of life runs deep after working many years with patients and their families in the hospice setting. These very experiences now inform Surratt’s photographic work as she still works through the emotional impact.

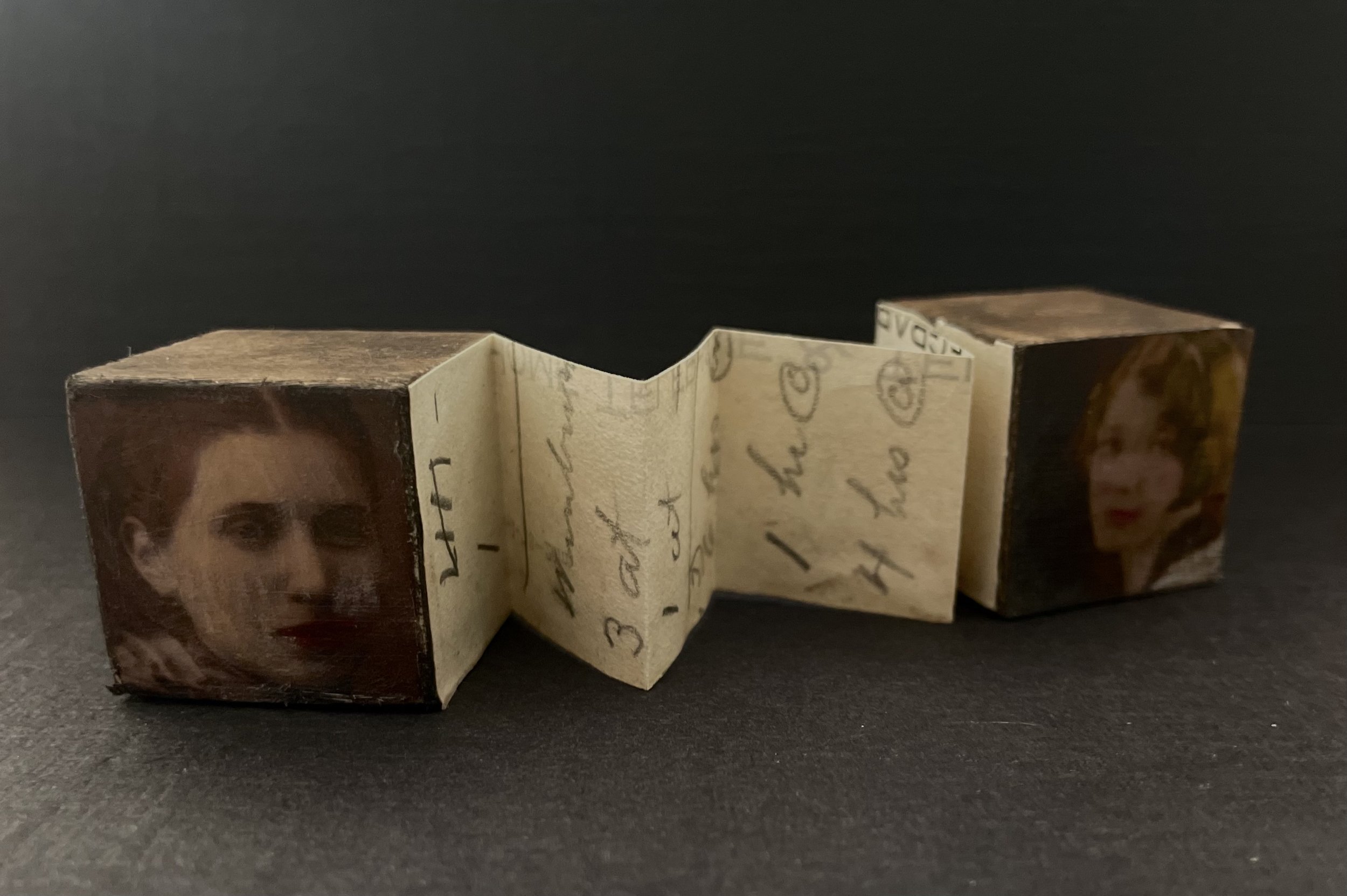

The Maine Museum of Photographic Arts’ current exhibition, Morphing Medium includes Surratt’s exquisitely crafted installation, Ephemerality. Piecing together antique objects with distressed photographic prints, Surratt guides the viewer to seek out the physical bits and pieces that hold fleeting memories of loved ones. The installation spans ninety-three inches of gallery wall, and is best experienced up close to take in the intricate details of each vignette contained within. For example, a stack of formal invitations with yellowed paper, ragged edges and bound in twine is held just above an open book with a hand-colored portrait of a woman, sliced into repetitive sections of an accordion fold. This seems to present multiple facets of a woman’s life, possibly a literary career interrupted by marriage. Through this suggestion, a memory is conjured — a faint reminder of someone in my own family tree left in the tattered edges of letters and photographs sleeping in the far reaches of the attic.

My family moved around a lot while I was growing up, but the thing that remained constant with me is my love of art. I studied under a Spencer Love Scholarship for Visual Arts at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and received a Bachelor’s degree in Studio Art. Shortly after I graduated, my father was killed in an accident. The intense work of personal grief compelled me to work with other grieving people and I pursued a Bachelor and Master’s degree in Social Work from the University of Georgia. I worked with hospice patients and families in urban and rural settings for the next 22 years. The backbone of my art is a direct outcome of that intimate work and the sacred witnessing of the human condition. It forever changed me and my work. Now I have now returned back to my first love of art and am a full time artist and photographer.

My imagery is emotionally charged and it is deeply influenced by the work of pictorialist and non-traditional photographers. I seek to bridge the viewer to quiet, internal dialogues through the use of digital manipulation and non-traditional camera lenses to create moody and painterly like images. I create in smaller scale to enhance a feeling of intimacy in my work but in the past two years, I have been incorporating my imagery in site specific, large scale installations as a way of exploring and creating intimate spaces and allowing for visual meditations. I am currently exploring the energy of objects and how their tangibility can connect us to memory and emotion. Through the use of mediums such as silk, alternative substrates, wax and paper clay, I have been creating photography transfers and one of a kind objects and book structures.

I am currently working towards a self-published book with images and contemplations from my project Sweeping the Graves. I am also continuing to exhibit this work across the United States. This year, I began a new project called The Silent Year, which explores transition, spirituality and aging.

— Dawn Surratt

Dawn Surratt, Alchemy, 2022, Pigment print, 19 x 12 inches. $200

Interview with Dawn Surratt

By Jan Pieter van Voorst van Beest

Jan Pieter: During the early stages of your artistic career your photography consisted of mostly rather romantic, well crafted, soft focus, pictorial material. When the project, Prancing Snowflake began in 2015, an interesting narrative was introduced into your work and an element of storytelling appears. Can you tell us about how that happened and the importance of it?

Dawn: That was a big turning point for me that really helped my eyes see in a different way. I just happened upon a hunter one day. I saw a homestead that I loved, but there were “No Trespassing” signs everywhere. So I had to be very careful about where I was photographing. A hunter rode up in a jeep and said, “Hey, you wanna tour the homestead?” “I take care of this property.” So I jumped at the chance. While we were exploring the property, he pulled a key out of his pocket to one of the rooms. He said, “I wanna show you something that I don't show many people.” He opened up the locked room, and there was this stuffed albino deer there. It jolted me because I'm not in the hunting culture and don't really know anything about it. But what immediately struck me was the tenderness of his relationship to the deer that continues. He had loved it. He had named it. He and his wife had bought special seed for him and everything. And then, the anguish of him having the realization that he would have to kill this deer or else it would be mutilated by other hunters, when they found out there was an albino deer in the area. The other hunters were all avid to kill him. Yet the couple’s relationship to the deer was so strong that they couldn’t just abruptly sever their connection. Through the grieving process, we try to preserve our relationship to the deceased with memories which can be triggered by mementos, in this case the actual deer, preserved.

So, I felt challenged to tell this story in a way that was going to marry these contradictory elements of this grief that we have with things that we've lost and how we identify ourselves with people who have already died. Even after death, there is an ongoing relationship there that seems universal. There was also this very personal element too, and I wanted to address the emotional aspect of it, but also the horror. So all these very disparate emotions became integral to my photography. It was the first time that I was able to think about my style of photography as a way to express these emotions. I worked through how to tell the story and while implementing both the literal and emotional aspects. While not being a documentary photographer, I had to see the pieces to that story in different ways and photograph them in a new way. So that helped me grow and stretch a lot in terms of understanding that I can branch out into different photographic styles and hopefully tell the story.

Dawn Surratt, Prancing Snowflake, 2016, Pigment print, 12 x 12 inches

Jan Pieter: As your career progresses you increasingly add more installation work and your work becomes more three dimensional with the increasing use of mixed media. How did the introduction of different media into your work happen?

Dawn: My first major was in studio art, and that's a broad degree. So I had a wide exposure to a lot of different mediums, not just photography. Though photography was probably my primary focus, I loved experimenting with a lot of other mediums too. I was never satisfied with just a plain photograph. I liked to play around with hand coloring and transfers and all of those things on fabric and all kinds of papers ever since I began making art. So that became a natural evolution for me to push out into different mediums and see how to incorporate photographs in different ways.

Jan Pieter: Christian Boltanski has done major work mixing the written word and his photography into three dimensional installations. Has he, or other artists influenced your work? Which other artists have had an impact on your artistic vision?

Dawn: I just recently became familiar with Boltanski’s work, so he was not the initial inspiration for me moving into the written word with the work that I make. Actually it was Duane Michals, who was the very first artist that kicked me into the idea of using image and word. I first learned of Michals’ work while in college and I just loved the way he intensified his images with the use of text, either overtly or implicitly in the concepts he was portraying through the storytelling component. In addition, I was so smitten and still am with the Dada artist movement—the way that the artists in that period of time just pushed out boundaries with text, collage, object work… All of those things. Then there are numerous book artists that I admire and inspire me to explore that world all the time

Dawn Surratt, Exchange, 2018, Ephemera, wood, oil stick, 1 x 5 inches. $175.

Dawn Surratt, Discourse, 2021, Wood, film, colored pencil, oil & paper, 1 x 1 x 3 inches, $175

Jan Pieter: You also seem to increasingly incorporate the written word/text and thoughts. When this happens, what usually comes first, the written word (language) matching the physical image or the reverse? What is the process?

Dawn: I really like the tension and marriage of the written word and physical image. They’ve co-existed for years in books. Yeah. And I just think that there's beauty in the text itself, the font, the size, the, the text block. So whether, the text is actually saying something or, or it's just used as a design element. I think it's interesting, but in terms of, of marrying the two, you know, I'll just take for instance what I'm working on right now. Sal Taylor Kydd and I collaborated on a writing and photography project through the pandemic titled, Touchstones. She sat me down and made me write poetry and we exchanged poems and images in kind of a call and response method. This collaborative work was just published in the book, A Passing Song. Thinking back on the experience now, words and images really saved us as friends and humans during this two year pandemic. I had a lot of grief and all of those things that fueled my words. Sometimes I wasn't fully aware of what was going on in my photographs at the moment they were made. Writing allowed me to draw on those thoughts and emotions to better understand how I was representing them visually. Images generally come first intuitively, but they’re not fully resolved until the ideas more fully realized as a period of time passes. It seems that in this case there was a balance between word and image as each was evolving through the back and forth process.

Dawn Surratt, Tapestry, 2018, Found objects, silk, ephemera, 12 x 6 feet

Jan Pieter: In some of your pieces you co-operate with other artists (The Meditation Walls, Touchstones). Tell us how you co-operate with other artists and how you weave it all into one coherent piece of art?

Dawn: The first time that I used the meditation wall as a real cooperation with a lot of other artists was in Murmuration, which was a show that I was in with, I think there was six of us all together. I knew that I wanted to do a meditation wall to bring together this idea of Murmuration, which is a large body of separate energies moving as one, which we all were. And so I asked the artists if they would be willing to send me objects or images that were important to them that I can incorporate into the meditation wall. It kind of then became the metaphor for murmuration. I used a few things from all the other artists, but most of it was mine. But I wanted all of them to be included as well. And then it took off from there. The meditation wall that I did for Kindred, which was with four artists, was about the weaving together of four women as friends, as mothers and as artists in all of the things in that bind us together. So it was really like a tapestry. I really do love collaborations. I love working with other people in the community because I learn so much as our individual building blocks come together to create the final piece. And in the instance of collaborating with one other person it becomes an interesting dance as equal partners.

Jan Pieter: Much of your work is inspired by your experiences in hospice work and end of life journeys. (Sweeping the Graves). With the progression of your artistic path how do you see your subject matter change and do you see different sources of inspiration appearing to influence your artistic endeavors?

Dawn: I think that's a great question because I've been thinking a lot about that. When I worked at hospice as a social worker, it's a professional position so you go in there and you have a very specific role. You are there for the families and you are kept hidden under this role. So your self disclosure is kept here. You don't really have time to interpret the things that have happened to the family, then you just go on. Since I stepped away from doing hospice work, it's taken all these years for that experience to filter down through my consciousness. I think that it will be informing my work forever, honestly.

Especially now, in this time of pandemic, worldwide strife, institutional grief that is just blanketing all of us— I ask, how do I then take my art and the things that I know about grief and end of life and use it to serve the community?

So when Sweeping the Graves came along, that was a project that I felt very compelled to do because it honored the the actual families that I worked with. A lot of the things that they told me and things that I learned from them and their grace and their amazing ability to withstand, tremendous stress of caregiving and saying goodbye.

As time passed, I began to understand that I wanted to create a place for the viewer to come and bring their grief and their sadness to a place to honor. So I think from this point on I will be looking at using art to create places for memorials and things like that that people can use to feel connected to one another and to the grief.

In Sweeping the Graves, there was an interactive piece that I did with an image in a frame that was shadow boxed with branches inside that people could tie white ribbon on in honor of loved ones. At the end of the show I came back to de-install and there were not only ribbons, but people had taken gum wrappers, tissue and everything they could find to tie on the twigs. It was so moving and let me know that people have a need for expressing that. It was really beautiful the way that people were very hushed when they came to see Sweeping the Graves. And so I see my art and the way that I am going to be doing art in the future as hopefully a way of healing, or a way of providing support and emotional resonance to people going through this tremendous grief because, you know, we're a very fast paced society and we just, we just move on so quickly. We say, Okay the pandemic is over. Okay everybody back to normal. But there are so many hurting people, including me and my family who suffered a great loss during the pandemic.

Grief is a universal language. I want to give viewers, especially those who are grieving in some way, a place where they can see something beautiful that might remind them of memories or provide something that gives them pause, that gives them a chance to be quiet and still in a crazy filled day.

Dawn Surratt, Memento Mori, 2018, Ephemera, found objects, 6 x 3 feet

Dawn Surratt, Reliquary, 2016, Pigment print, 12 x 6 inches

Dawn Surratt, Reliquary #2, 2021, Found objects, cold wax pigment, ephemera, 13 x 4 inches

Dawn Surratt, As I Am You Will One Day Be, 2018, found photographs, teabags, wax, wood, 8 x 3 inches

Dawn Surratt, Confluence, 2018, Pigment print 16 x 9 inches