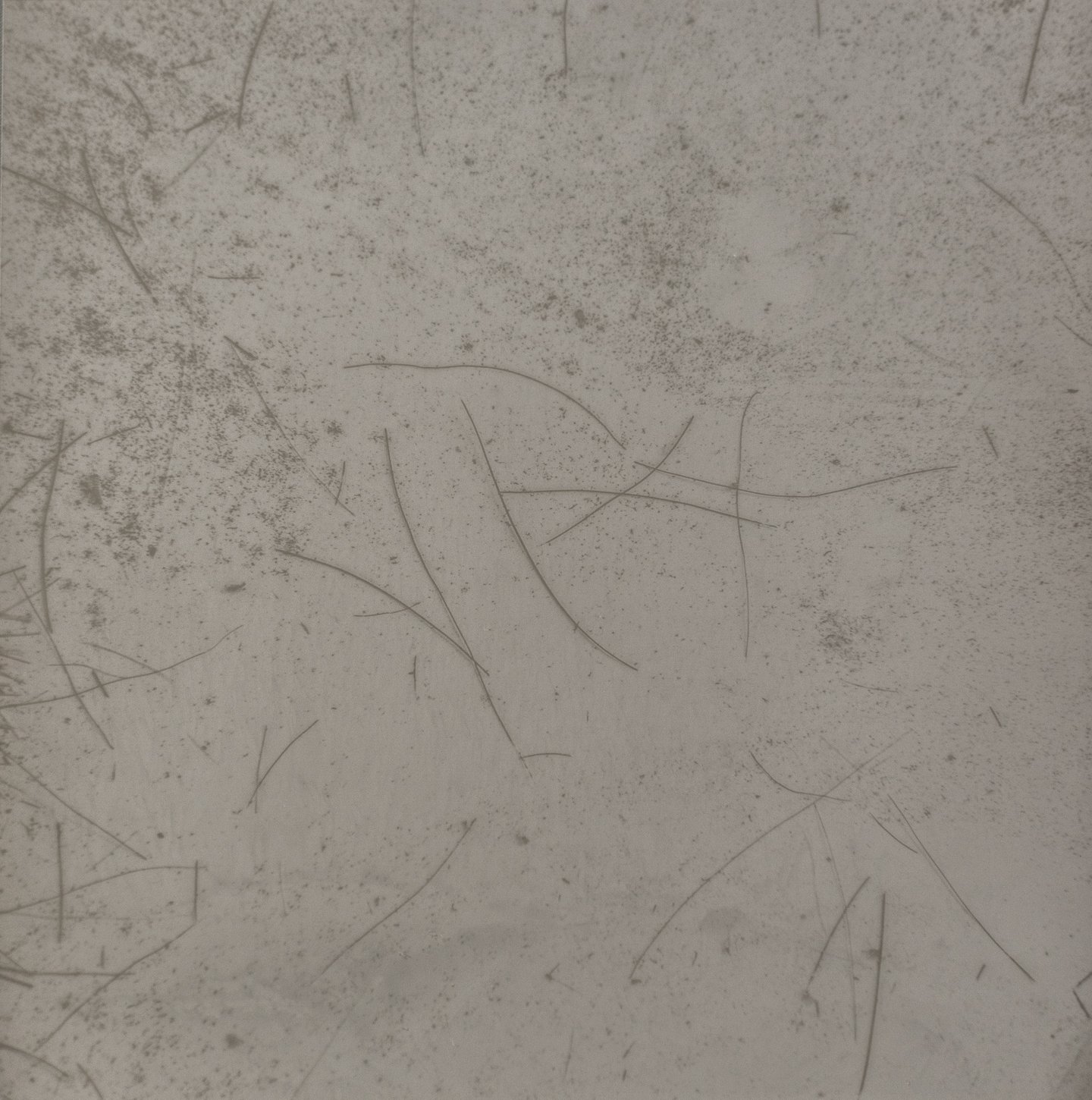

Brendan Bullock, Draftsman's Brush Bristles #1, Camden ME, Silver gelatin print 2022, 1/1, 9.75 x 9.75 inches, $1800

After my father passed away, I remember going into his over-crowded woodshop and looking at all the things he’d left behind. Curly maple shavings still lying next to a plane, dimensions and mathematics scrawled on the backs of envelopes, coffee cans full of nuts and bolts.

When I walked into an abandoned boathouse in Camden Maine on a commercial assignment recently, I found a strikingly similar scene, with even more of an aged patina. It was as if at noon on a Tuesday in 1990, everyone had gone out for lunch and never come back. Sawdust. Cobwebs. Blueprints. Plywood jigs and cutouts. Unfinished projects. In the office, I pulled out the top drawer where the draftsman had worked. Over a few decades of mice passing through the drawers, his bench brush had had its bristles broken, chewed on, and scattered around. Seeing them so beautifully distributed felt like finding a treasure.

For years I have made this kind of abstraction while en route to making other work. The Cleveland Rooftop piece in this series was made while photographing the Republican National Convention. The wall detail from Tanzania was made while spending a couple weeks photographing within a rural Maasai community. It didn’t occur to me until recently that the human hand always plays a role in these compositions I perpetually seek, directly or indirectly. How the mice scattered the bristles is the beautiful part, but they wouldn’t exist if a man hadn’t left a brush in the drawer in the first place.

I’m spending more time these days thinking about what we all leave behind – artifacts, traces, influences… and the way in which even the mundane, given enough time to sit and age, can transform into something profound.

– Brendan Bullock

Brendan Bullock is a fine art photographer based in Bowdoinham, Maine. A decade of work in the world of fine art galleries, spending time around paintings and works on paper, ultimately inspired very specific interests within the realm of photography. Primary among those are creating unique prints, mixing mediums, combining digital images with historic printing processes, and experimenting with organic toners. A portrait photographer by trade, Bullock focuses his fine art work largely on abstraction, sourced either in nature, or found in man made materials.

Jan Pieter interviews Brendon Bullock

J.P: Having a four artist abstract exposition becomes interesting when exploring the approach of each artist to the project. In your work I find different directions. Some of the work seems “found” and subject to sudden intuitive recognition of the subject matter (Mostly in the work shown here), whereas in other projects there seems to be a predetermined direction when exploring your subject matter. (Viruses, and also in the Newfoundland Ghost Town Series) Can you enlighten us where and when the approach to certain subject matter starts?

Brendan: I have never been very project driven in my work, for better or worse–for the most part I have photographed whatever has interested me at the time and then later looked for cohesive ideas and recurring themes within that work. I’ve been influenced by certain aesthetics outside the realm of photography- abstract expressionism and minimalism come to mind- I think that these influences have played a large part in what I seek out visually in the world, photographically. With this series of abstract work the commonality of through- line is a certain subject that has been created or affected by the human hand in some way, and then that subject has evolved due to the effects of time. As I wrote in my artist statement for this show, the images of the draftsmen’s brush bristles I found in a desk drawer were beautiful because mice had chewed on them and scattered them over time- they were ultimately responsible for the arrangement, but the arrangement would never have been created without one man making a brush and another man leaving that brush in a drawer for three decades.

I have always felt strongly that the natural world is the most interesting creator, and natural patters have always fascinated me. (I am imagining the patterns of a river delta in sand, or perhaps frost on glass, or even the outward pattern that mycelium creates when it spreads.) These patterns are more free-form than something purely geometric like a honeycomb or a Fibonacci- driven design, but they still observe certain parameters. What I like about these abstract pieces, such as the brush bristle images I mentioned, is that there is an elegance to the way that the lines are distributed in the image, but as a visual statement, the arrangement is not predictable, nor does it contain any symmetry. The effect of nature’s reclaiming of something built by man (the mice and the brush) was the organizing principle of the patterning left behind, but that patterning does not follow any parameters- it’s essentially a beautifully organized chaos.

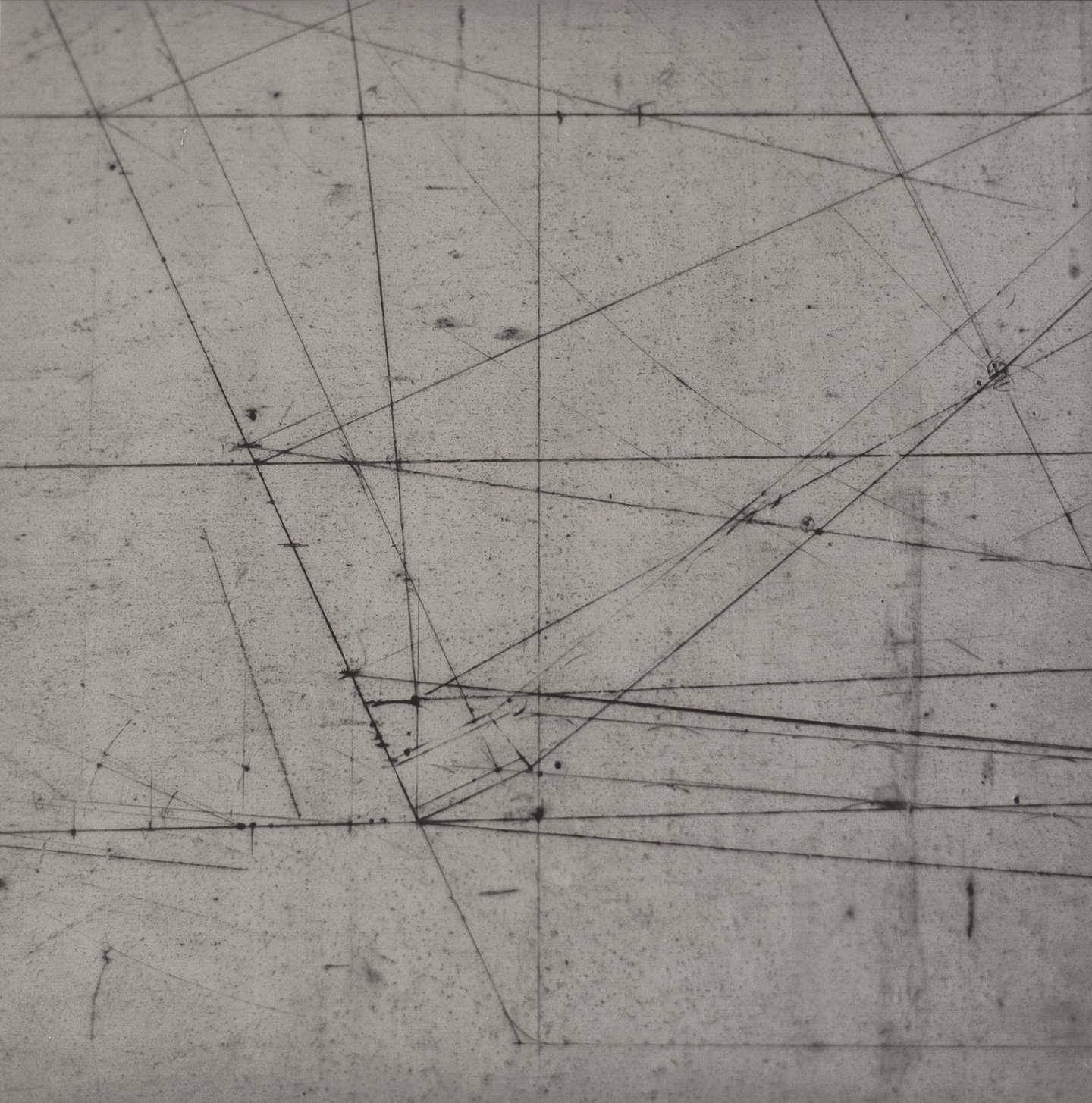

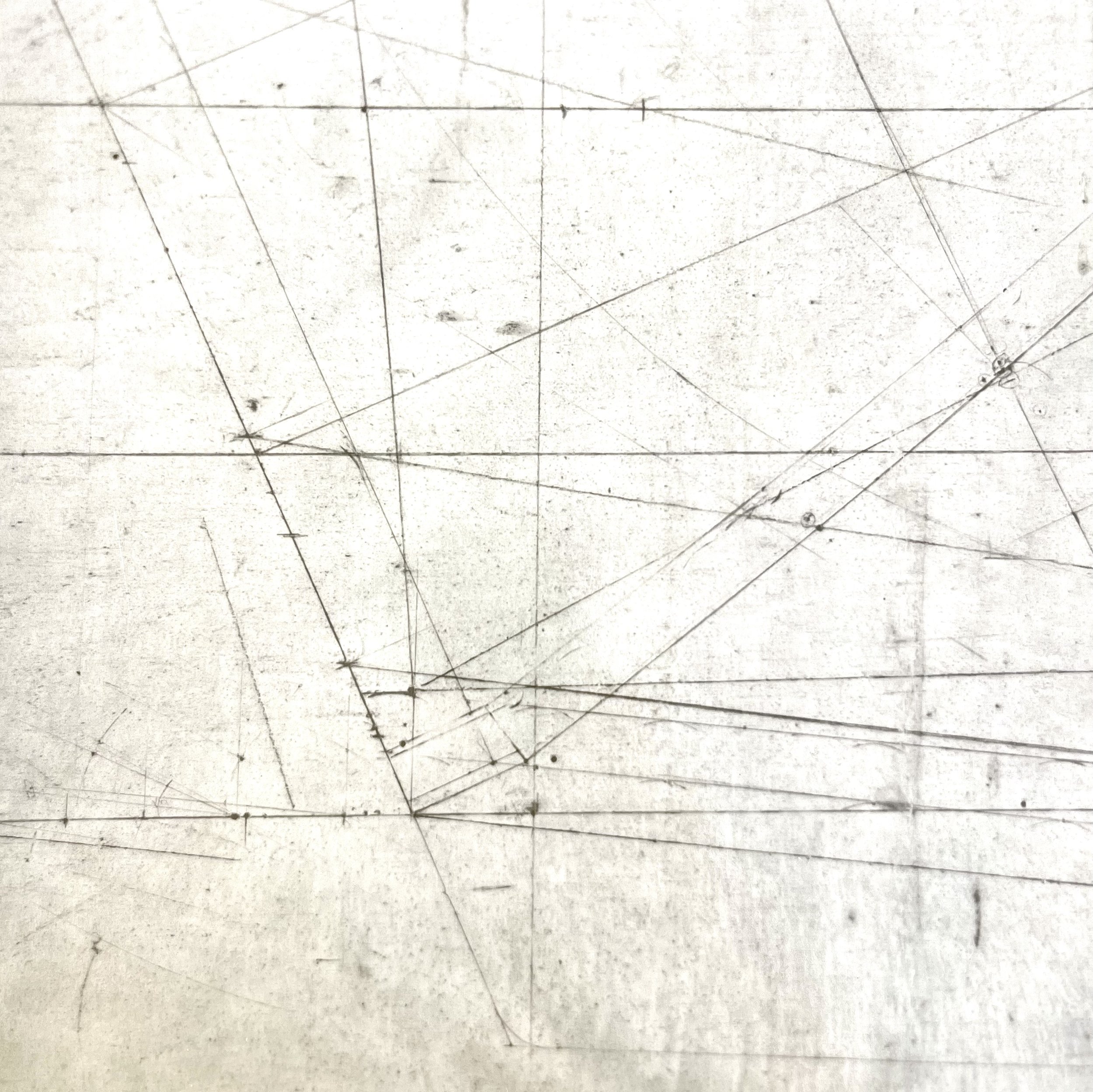

J.P: When looking at the different editions of your image lists I see that some of these images were initially printed on (probably) out- dated photographic papers where in the end they were finally printed on silver gelatin paper with hand applied emulsion. Could you tell us about your choices of the chosen substrate material?

Brendan: I have been experimenting with a lot of expired papers recently—my attraction to them was driven by my current interest in creating unique works, and my creative dissatisfaction with the mass-reproducibility of the digital medium. Watching prints come out of a printer does not satisfy me, even though the end result can be beautiful. Watching a print emerge in chemistry or watching paper develop in the sun is deeply satisfying, and often mysterious.. Sometimes things happen that can’t be duplicated, whether intentionally or accidentally, and that becomes a part of that particular print’s magic and value.

Knowing that I wanted to create unique prints moving forward, but still planning on making images using digital negatives, I decided I would experiment with expired papers precisely because the results would be unpredictable. I have printed with papers as old as 1940 and have found some of my favorite papers to be from the late 1960s and the early 1970s—specifically warm tone silver papers. Initially I printed this abstract series on a variety of different papers, using both expired and modern chemistry. This yielded quite a number of very interesting prints, no two alike. For this show however, I decided that I wanted the prints to have a somewhat uniform tonality, and since that was nearly impossible to achieve with the expired papers. I ended printing these images on a modern, Ilford, warm tone silver paper. As I continue creating this work, I’d eventually like to have an exhibition of prints that all vary in color tone, and I’d enjoy figuring out an interesting way to hang them all together such that the color variations themselves created an interesting composition on the wall.

J.P: A lot of photographic approaches depend on a certain “Decisive Moment” that tells the photographer that the time of the photograph is “Now”. Generally for street and portrait work this is rather clear but it seems that even in still life or landscape photography this plays an important role. I feel that this happens as well with some abstract work. Do you feel there is a “Decisive Moment” element in your approach?

Brendan: Earlier I mentioned organized chaos, and that idea is a connection between this abstract work and the journalistic photography that I have done professionally. With street photography or journalism, we have the idea of the decisive moment- when all of the elements of a scene fall into their respective places and create a beautiful visual order. It involves seeing quickly, but also involves seeing widely, watching all the building blocks of a composition come together till the instant the brain tells you that everything has achieved a good order. This abstract work does not involve seeing quickly- in fact the work is made relatively slowly. But when filling the frame with found detail, I still find a decisive moment of sorts when the specific positioning of the camera’s frame brings a cohesive or a pleasant order to a composition. The commonality between a fast, journalistic decisive moment, and a slow, pensive abstract composition, is that in both cases, it’s the observation of chaos becoming ordered that pleases one enough to click the shutter.

The best way for me to describe it—look out at the room that you are currently in, and now force yourself, staring straight ahead, to look at both the floor and the ceiling simultaneously. You will notice, that when you do, nothing is perfectly in focus because you’re telling your eyes to look at two things simultaneously that are spatially distant from one another. In this state of seeing, you can still observe all the shapes that are in the space with you, and if those shapes were moving, you’d still be able to make out their general forms. In the case of street photography, clearly you can’t observe every single individual detail in your frame while it is moving and wait until you like the characteristics of each–you’d miss your moment. When seeing widely and observing the overall juxtaposition of shapes within the frame, your brain will tell you when a good order has been achieved, or actually, that a good order is about to be achieved, giving you the anticipation needed to click the shutter at the right time. Thinking about photographing the brush bristles in the drawer, I remember un-focusing my eyes in this way and just hovering over the scene, slowly moving until I felt a visual order of sorts had been achieved.

J.P: Some abstract photographers build their photographs by adding and manipulating different elements (nowadays in different layers) into one piece of work. Others find their subject matter as is and present it by just framing what they find. As you say in your statement, you find order in chaos. Tell us about your approach.

Brendan: As I mentioned, these works are created with digital negatives- that’s a digital image that had been printed out on a clear acetate substrate, which is then contact printed directly onto paper. The beauty of working with this process is that you can use the precision of digital editing to do your dodging and burning and handle your contrast, but you can then render the negative with any number of analog processes, creating wildly different results. However, outside of editing saturation, contrast etc., these images have not been digitally manipulated from their original state.