We’ve identified some properties that might fit. We’ve reached out to entities that might want to collaborate. We’re in the process of bank proposals. Your dollars are needed now more than ever—As are your connections, affiliations, your support and encouragement. Please give like you mean it this season, so that we might give back with excellent programing, outreach, education, appreciation of the artists in this state, and opportunity. Are you on the advisory board? Shouldn’t you be? - Director, Denise Froehlich

Lucy Lippard: All Over the Place

Each time we enter a new place, we become one of the ingredients of an existing hybridity, which is really what all “local places” consist of. By entering that hybrid, we change it; and in each situation we may play a different role. The intersections of nature, culture, history, and ideology form the ground on which we stand—our land, our place, the local. The lure of the local is the pull of place that operates on each of us, exposing our politics and our spiritual legacies. Inherent in the local is the concept of place—a portion of land/town/cityscape seen from the inside, the resonance of a specific location that is known and familiar. Most often place applies to our own “local”—entwined with personal memory, known or unknown histories, marks made in the land that provoke and evoke. Place is latitudinal and longitudinal within the map of a person’s life. It is temporal and spatial, personal and political. A layered location replete with human histories and memories, place has width as well as depth. It’s about connections, what surrounds it, what formed it, what happened there, what will happen three. For many, displacement is the factor that defines a colonized or expropriated place. And even if we can locate ourselves, we haven’t necessarily examined our place in, or our actual relationship to, that place. Yet our personal relationships to history and place form us, as individuals and groups, and in reciprocal ways we form them. Land, history, and culture meet in a multi-centered society that values place but cannot be limited to one view.

I use space here as a physical, sometimes experiential, component. If space is where culture is lived, then place is the result of their union.

Cole Caswell

Rise is a photographic investigation of the coastal landscape in Maine that will be lost to sea level rise. Made using the wet-plate collodion process the images depict places that will be underwater or rendered unrecognizable by the turn of the century. Reclaimed by the ocean.

Cole Caswell, Spurwink River South, Plate 007, From the Rise portfolio, Pigment Print from Glass Plate Negative, 2021

My sense of home is tethered to an island off the coast of Maine. A landscape often battered by wind, drenched in waves, and enveloped in fog. The coastline of Maine has always felt like a mystical place for me, dotted by marshes, lagoons, and islands. Romantic and full of history this place where sea meets land is going to change in dramatic ways as our planet’s climate continues to warm. Predicted sea level rise is already affecting the coastline and by the end of the century the places described in these images will be underwater or changed beyond recognition. Reclaimed by the ocean. My use of the wet-plate collodion process allows me to hand make each of these images while on location. The resulting glass-plate negatives are an accumulation of what it is like to be in a place – a tribute to a landscape that will be consumed by water and the rising ocean. The artifacts and unique marks within the hand poured negatives intrigue me. As chance-based additions they visually suggest the faltering of our contemporary world. Maybe visions from memory, a dream, or a fleeting glimpse of what is at stake as our climate changes the places we hold sacred. CC

Cole Caswell, Halo, Plate H011, From the Rise portfolio, Pigment Print from Glass Plate Negative, 2021

“Whether we and our politicians know it or not, Nature is party to all our deals and decisions, and she has more votes, a longer memory, and a sterner sense of justice than we do.” ― Wendell Berry

Rose Marasco

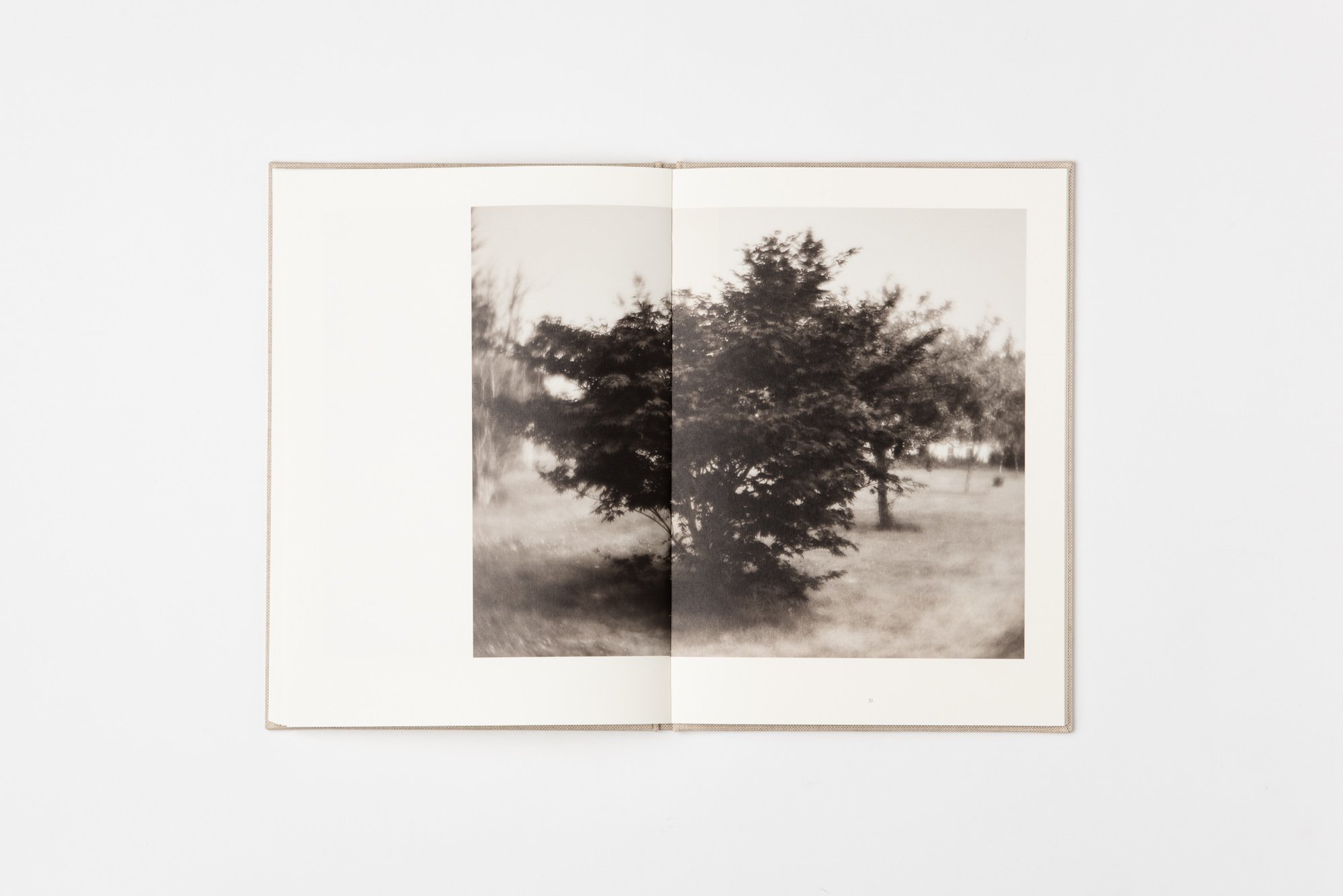

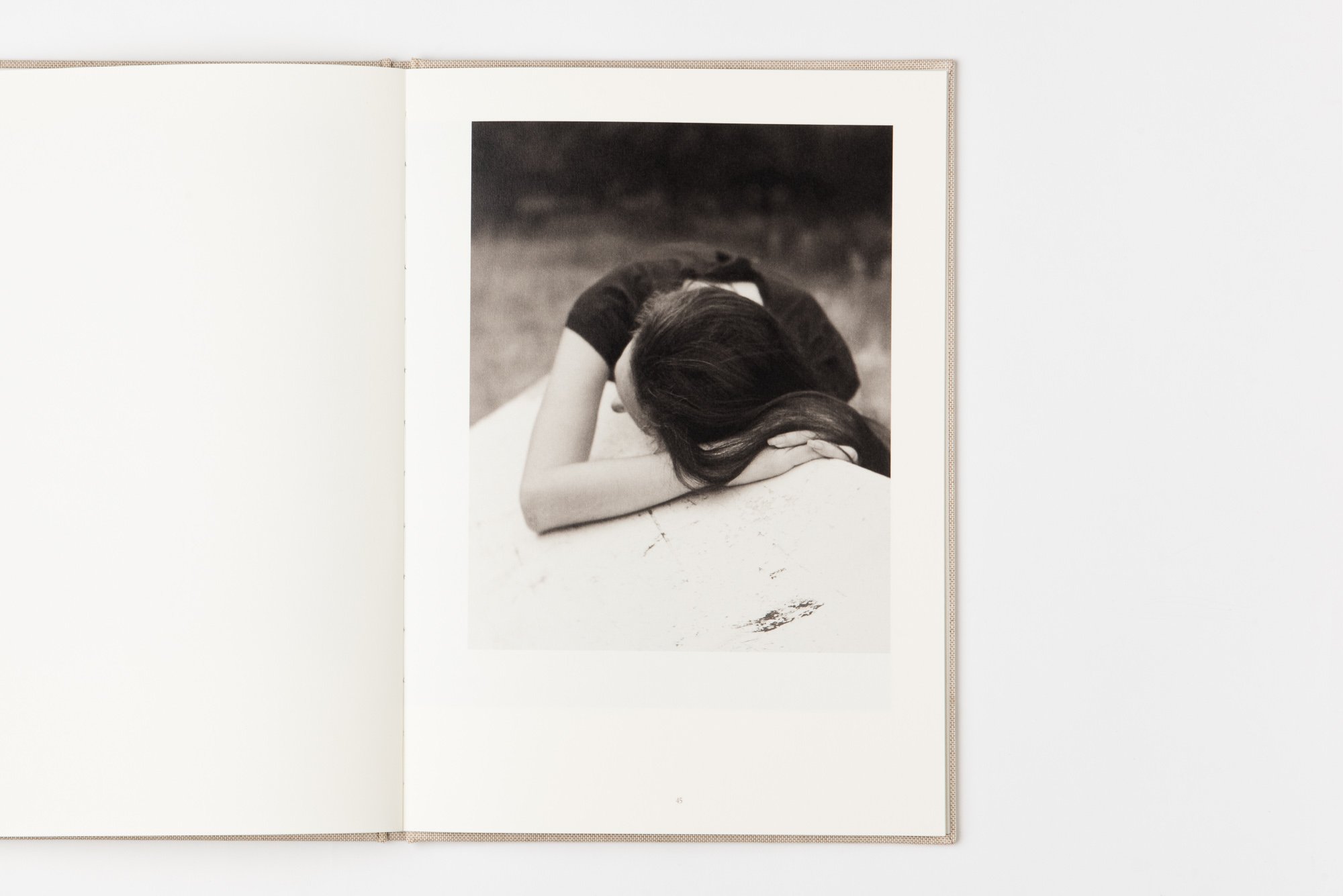

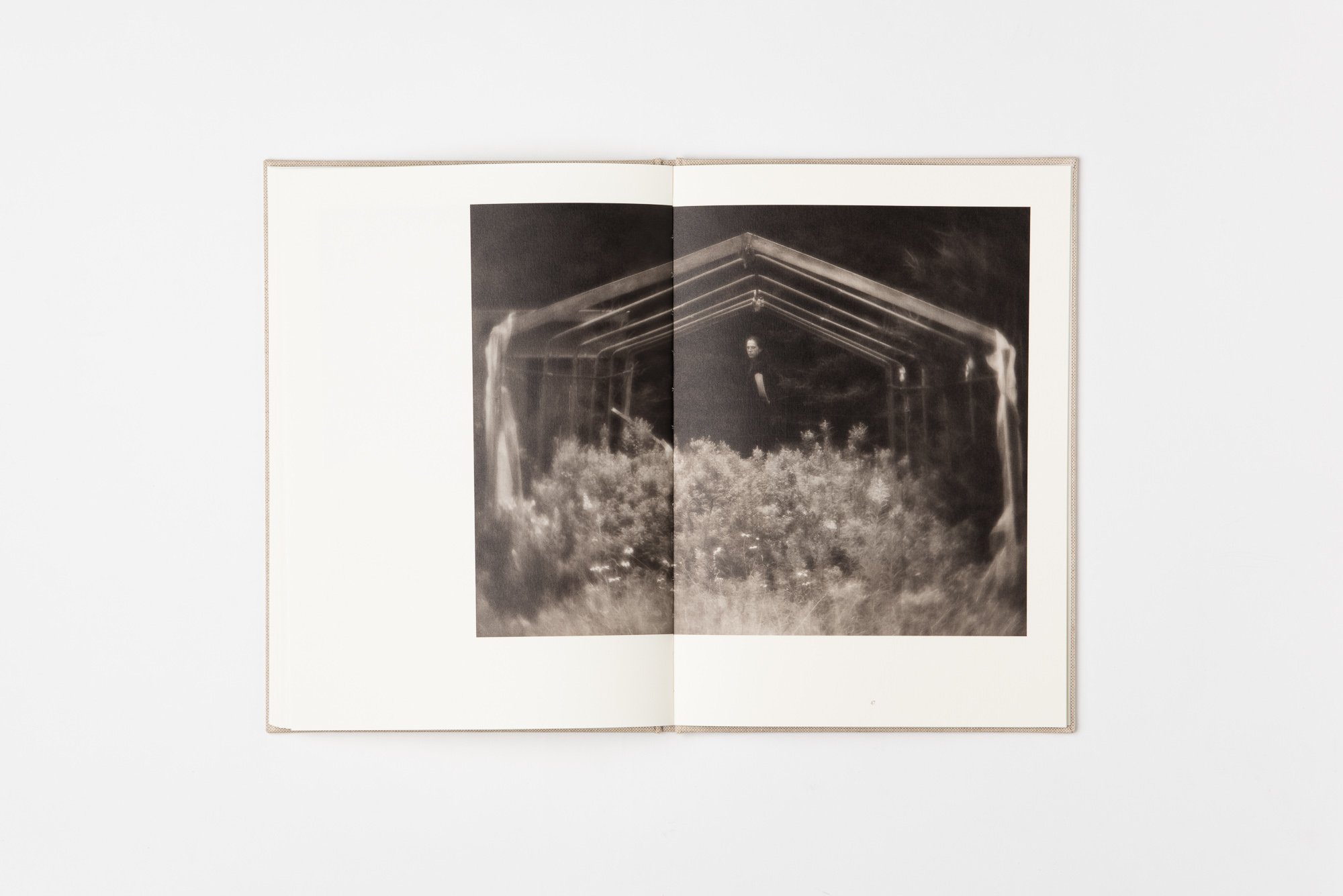

A new series called Parallax from Marasco’s up coming book entitled, At Home; Photography, History and Me.

Rose Marasco, From the series Parallax, 2020-21, Inkjet print, 12.5 x 20 inches

It’s late February 2020.

I decide to try photographing the houses/trees/shadow shapes again. I think maybe I’m looking up too much; and the perspective is throwing it off. Therefore, I put a ladder in my car and go around the block. I shoot the same film: medium format color negative film. But this time I decide to shoot square, intuitively thinking that the square may read as more abstract.

I drop off my exposed roll of film at the local camera store and have the twelve images printed 4x4 inches, on luster paper with a white border. When I pick up the film, I get to my car and immediately look at my prints. I like many of them!

Later at home I quickly lay out a sequence of nine that I think look pretty good together. The photographs are still of the same subject matter but, they read much more as a metaphor this time, especially when arranged in a sequence. I load another roll of film and walk around my neighborhood again. It’s now early March—yes, just before the coronavirus pandemic. I’m scheduled to go to The Tyrone Guthrie Center, an artist residency in Ireland, on March 26. I have been looking forward to this very much. I have my tickets, and all is in order—until it isn’t. Needless to say, everything gets cancelled.

My exposed second roll of film lives in my refrigerator, unprocessed, for at least a month or more. I have several former students, now friends, who volunteer to grocery shop and do occasional errands for me, and I feel very fortunate. Eventually I ask one friend if, when she goes to Photo Market, she’d drop off my film. “Sure,” she says, “I’ll be going soon.” I put the film in an envelope and write explicit directions as to the size, kind of paper, and the white borders I want. A long time goes by; I call the store and find out that not many people are going in to work and my film is still not done. A few days later, I finally get a call that it’s ready. I know the guy who calls me as he’s worked at the store for a while. It’s just about closing time when he calls, and uncharacteristically for me, I ask him where he lives— thinking if he lives near me maybe he’d drop my film off. I’m desperate to see this second roll!

“Oh, I live in Windham.” Nowhere near me.

“Why, where do you live?” he asks.

“I’m in Portland, in the West End.”

“Ok”, he says. “I’ll drop it off.”

“Really? But it’s way out of your way.” He insists, and I thank him very much. About 45 minutes later, he tosses the package onto my porch.

I’m extremely disappointed to find that they forgot the white borders, and the print color is off quite a bit. But suddenly, I forget about all that as I get an idea! I instantly start making the composite groupings of photographs you see here. With the borders gone, everything looks and feels much closer to how I was experiencing the multiplicity of the shadows on my walks.

A few weeks later I decide to go into my archive and find the older prints that I originally made as single images. I cut off the borders and make composites with these. Suddenly, they’re working too! To have any kind of breakthrough or forward movement in the endless days of the pandemic feels huge, and I am forever grateful. RM

“And so will be our family itself, our marriage, the children who enriched it, and the love that has carried us through so much. All this will be gone. What we hope will remain are these pictures telling our brief story, but what will last, beyond all of it, is the place.” - Sally Mann

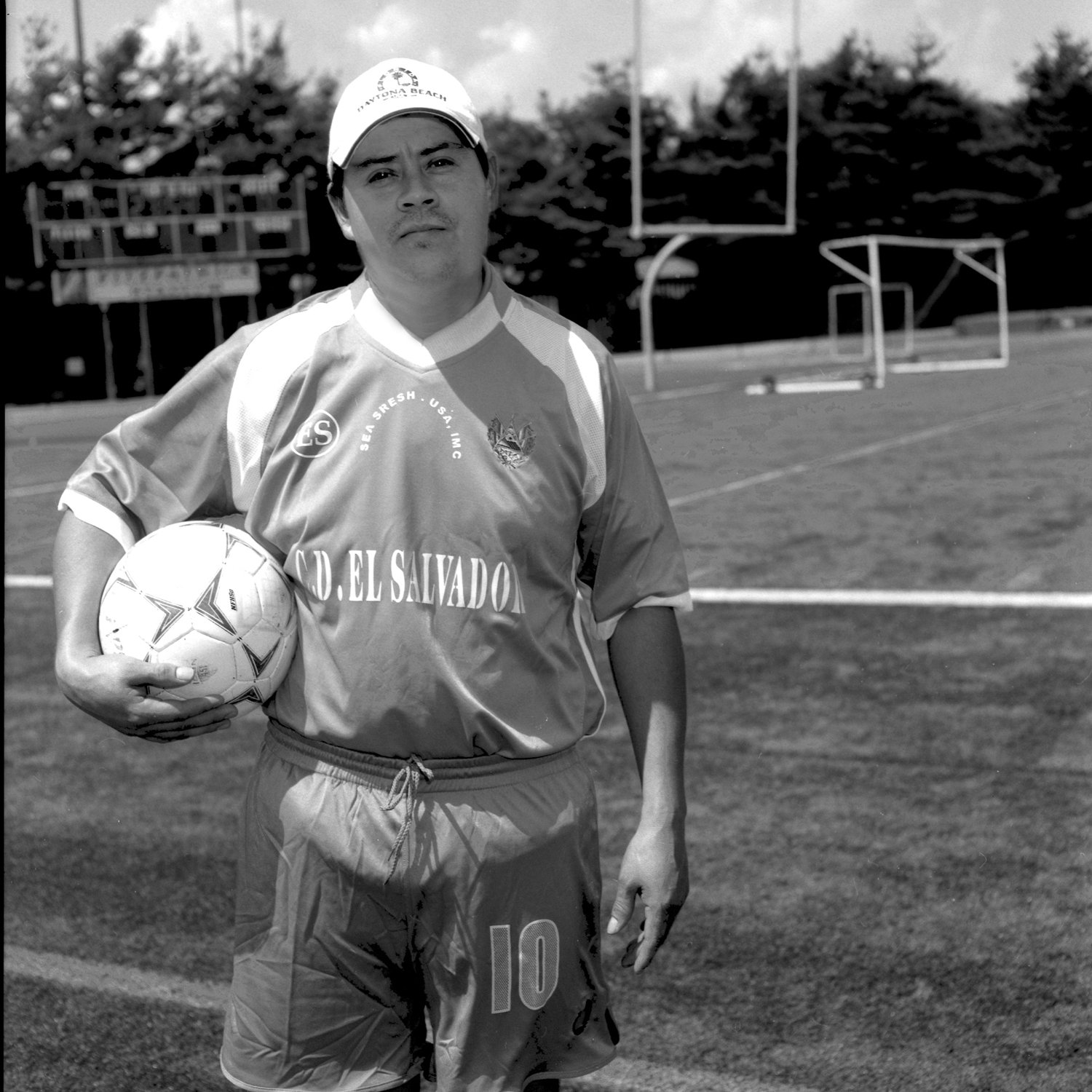

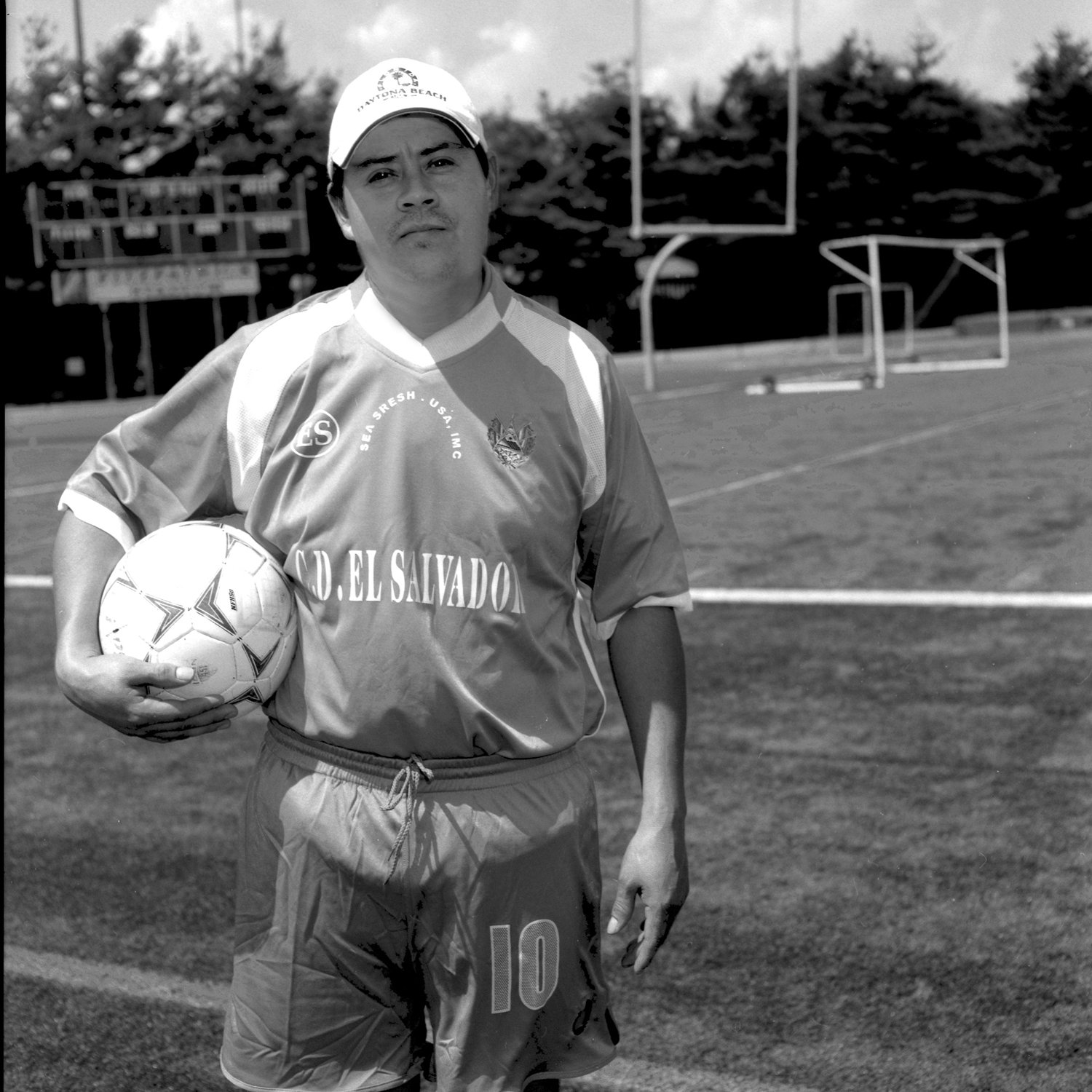

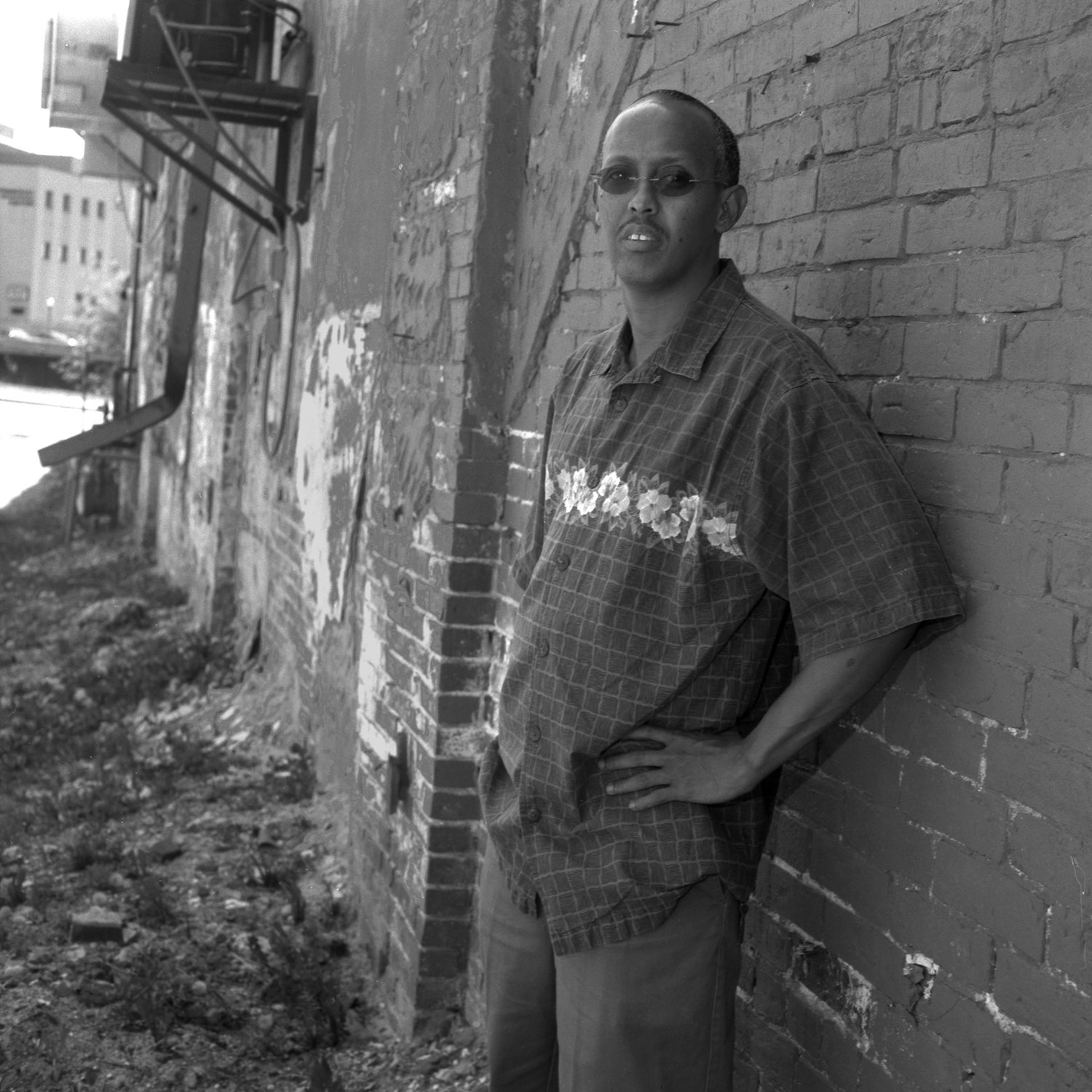

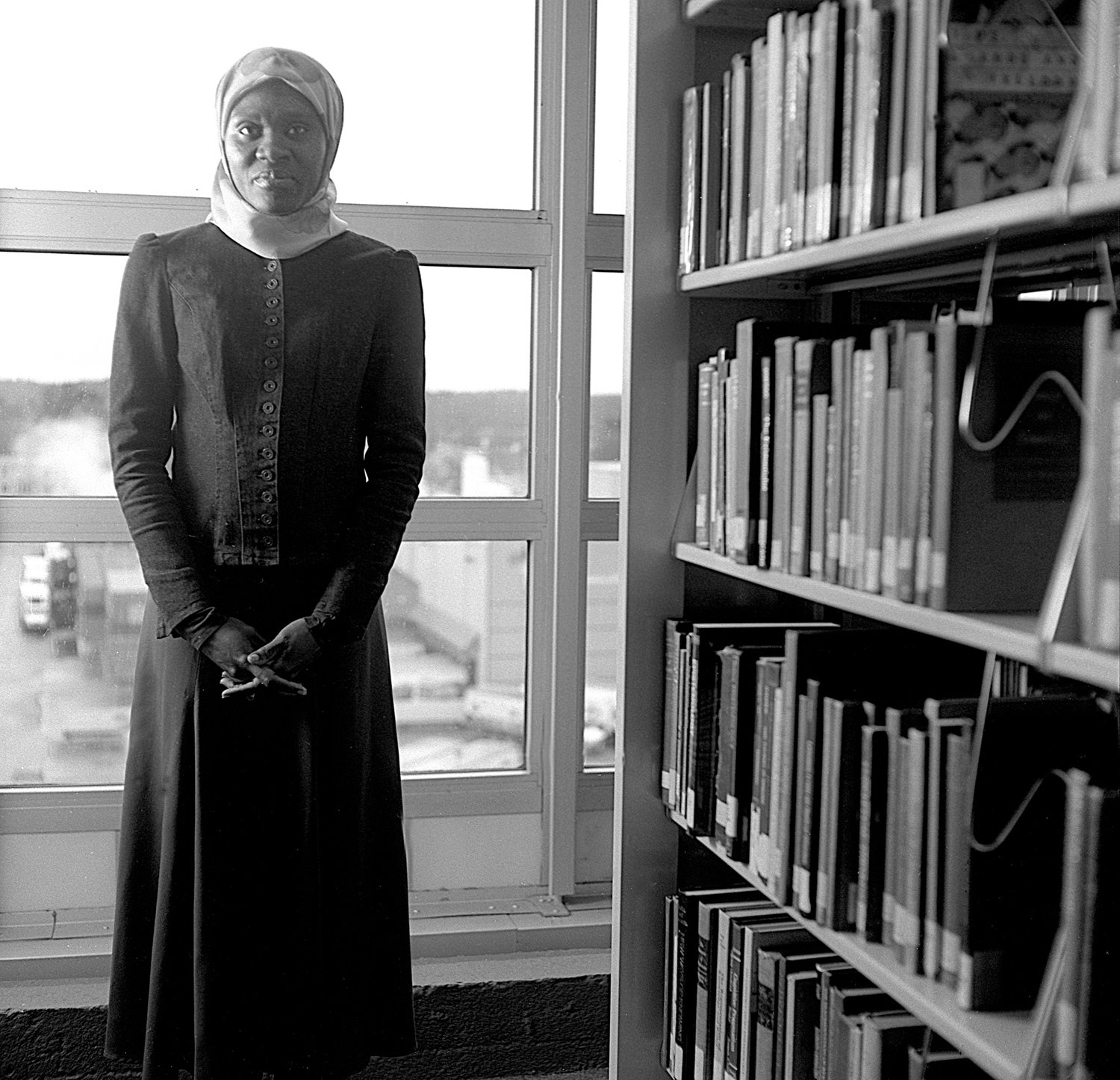

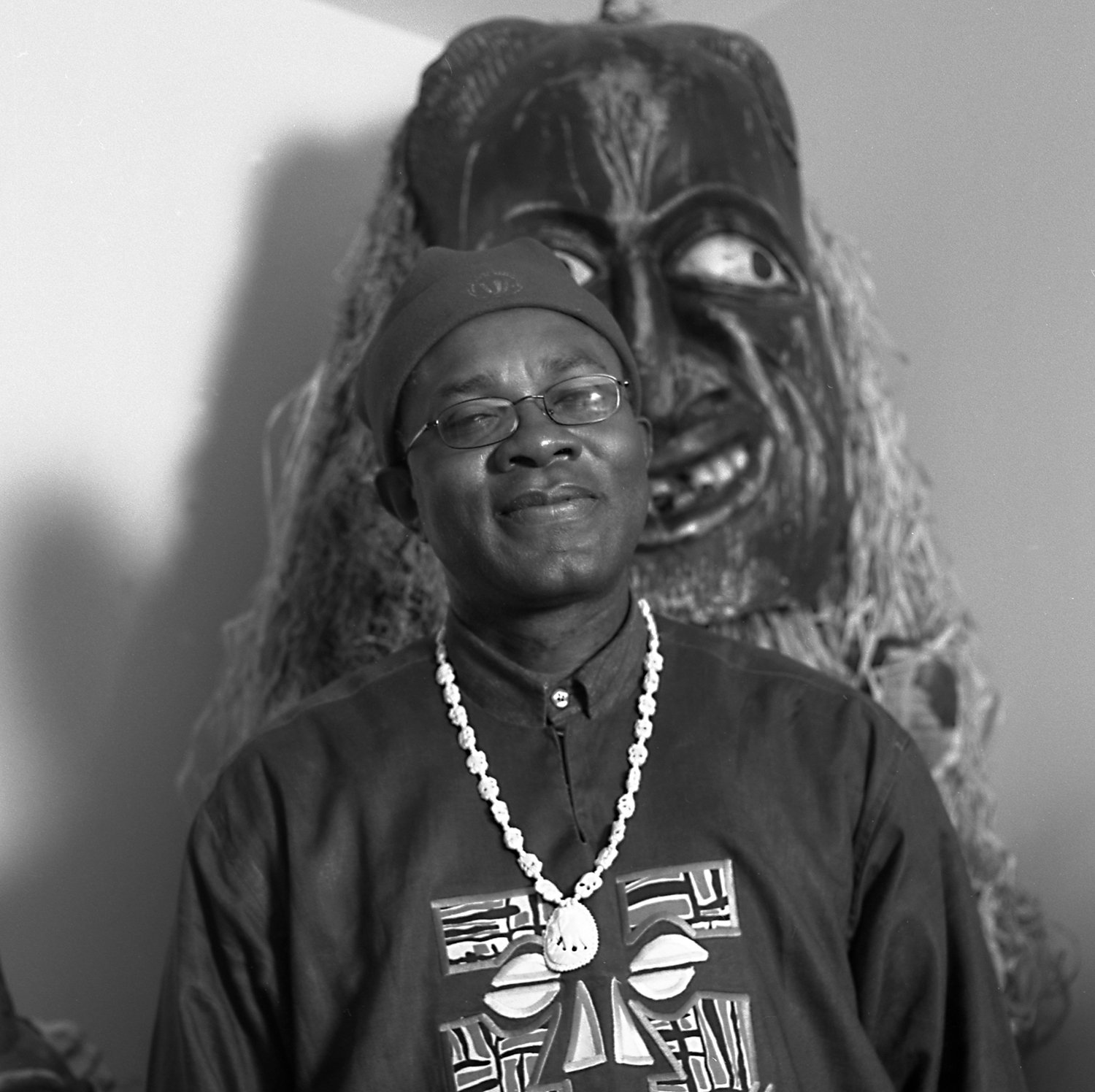

New Mainers; Portraits of our Immigrant neighbors

A look at the process of book making

New Mainers, Portraits of our Immigrant Neighbors,Photographs by Jan Pieter van Voorst van Beest, Text by Pat Nyhan, foreword by Reza Jalali. 8x10, 156 pages, Paper Back, edition of 3000 (almost sold out) Published in 2009 by Tilbury House Publishers.

Twelve Years Since New Mainers

by Jan Pieter van Voorst van Beest

As an immigrant and a photographer, I was always interested in the immigrant community that I used to see in Portland. I was also intrigued by the number of restaurants owned by immigrants in the city. I thought, how nice it would be to do a photo book about those business people—to photograph the owners in their kitchens or in front of their restaurants, have them write up one of their favorite recipes and then do a short interview with them about their history and about what brought them here. So I asked my friend Pat Nyhan if she would be interested in writing the text portion of such a book while I would illustrate each chapter with a black and white portrait of the person. At the time, Pat was a writer for the statewide weekly newspaper, “Maine Times”, and enthusiastically agreed.

We then set out to find a book publisher which required some research to find one that would be a good fit for this project. After carefully reviewing each publisher’s list of titles and genres, we decided to approach Tilbury House Publishers with our proposal. When submitting a book proposal it is best if you can actually talk to the publisher to make a personal connection. Though it is difficult to find a publisher to take your call, Jennifer Bunting of Tilbury House Publishers was an exception to the rule, as she would actually answer the phone herself. She was also extremely approachable and helpful. So we were lucky to get Jennifer on the phone… then have our idea rejected. Book proposals on restaurants are difficult because by the time your book is published, most of those restaurants would be out of business. Book rejected! (But not discouraged).

Because it was the restaurant piece that proved to be the undoing factor, Pat and I decided to eliminate it and just try to do a book focusing on immigrants in Maine. Don’t give up after your first rejection! Looking to expand on the diversity of immigrant stories, we contacted Reza Jalali, an immigrant from Iran, who at the time was the diversity director at USM. We asked him if he could help us contact immigrants from various backgrounds and arrange for them to be interviewed by Pat and photographed by me. He agreed.

When working with several people on a project like this, a collaboration agreement should be created to outline the responsibilities of each collaborator. In a case like ours, authorship and copyright depend on how substantial the individual contributions to the book are. Some collaborators may have done important work and should be mentioned but may not have authorship because of limitations of their contribution. In our agreement we agreed to split the proceeds of the book between Pat, Reza and me. Pat and I would be named the authors of the book while Reza would, in recognition of his contribution, write the foreword.

With our collaboration agreement established, we then decided to create a sample chapter which we hoped to present to Tilbury House Publishers. Makara Meng, the owner and operator of Mitpheap Market on Washington Avenue was our first subject. Makara is an immigrant from Cambodia and a survivor of the Khmer Rouge’s Killing Fields. Pat interviewed her and I created her portrait at her home in South Portland. After we put the chapter together we again contacted Tilbury Press. I got Jennifer on the phone and told her that we had heeded her advice, discarding the restaurant idea. This time, we put together a proof chapter just focusing on immigrants. To our surprise, she invited us to Gardiner for a presentation.

A half hour into our conversation Jennifer told us that she would publish the book! We had a strong proposal and approached the right publisher. Jennifer then sent us the Publishing Agreement which is important as it covers rights, copyright, indemnity, timelines, promotion and distribution, royalties and many other important matters. It is also of extreme importance to make sure there is total understanding about what the book will look like. Design considerations such as typography, image treatment, page size and orientation, paper type, and cover material are essential components to effectively convey the content of the book. Also, make sure there will be the opportunity to review press proofs to be sure photographs are printed with the correct tonal values. It is crucial for the prepress department to adjust the image curves based on paper type in order to match the photographer’s original intent. This is another stage in the publishing process where the photographer must collaborate with the designer to ensure image file conversions stay true to the original.

About a year after our first meeting with the publisher, the book was published. Pat interviewed twenty five immigrants, and I had portrait sessions with all subjects and created all the photographic material. I shot everything on 2 1/4 Tri-X film which I later converted to digital files for the publisher.

The day “New Mainers” came out we hosted a “book publishing” event at Hannaford Hall at the University of Southern Maine. The hall was filled, we had immigrant speakers and the photographs were projected on the big screen. That first night we sold and signed about 150 books out of an edition of 3000. At the same time there was an exhibit of the photographs in U.S.M.’s “Area” gallery across the street.

The book was an enormous success. It was wonderful to see it on the shelves of nearly every bookstore in Maine. It tells the stories of the “New Mainers”, showing where they came from and what their experiences were. It helped create an understanding of the difficulties many immigrants face and hopefully helped make their lives better. It also received great reviews and we held talks at schools, libraries and museums. We held book signing events at many book stores, were guest speakers at the Maine Literary Festival in Rockland and even had several minutes of fame with an appearance on the television program, 207.

The term “New Mainers” took on a life of its own. Immigrants to Maine are now often referred to as “New Mainers” and the term was adopted by others in newspaper articles and even a radio program. Now, after having had the book in the stores for twelve years, the edition has almost sold out. I have shown the photographs in many exhibits, galleries, museums, schools and libraries.

Overall, I have enjoyed doing the book. I am an immigrant and the book is for immigrants. It was great to talk to and work with the subjects, to get to know them, listen to their heroic stories and to photograph them. There are also a few lessons for photographers wanting to publish their work. Research the publisher to find a good match. Make sure you agree with your collaborators on the smallest details, especially about authorship, money and copyright. Get the design details of the book cleared up and understood early in the process. Make sure your subjects sign a model release!

After twelve years, the edition is now almost sold out although recently I still saw one on the bookshelves of a local bookstore. You can also find it on Amazon, at a slight discount!

“New Mainers”

Deb Dawson Interviews writer Pat Nyhan

Even with many great self-publishing options today, choosing to use a publisher has many advantages that facilitate better design and distribution of your book to get it to the right audience. But regardless of how the book is published it’s the content and story that helps it stand the test of time. Reading “New Mainers” now is just as relevant today as it was twelve years ago. As we continue to welcome immigrants from around the world fleeing persecution, war, famine, or seeking a better economic life, we can all strive for greater understanding and compassion by listening to their stories of survival. Wanting to learn more about how these stories were gathered, I reached out to Pat Nyhan to learn more about her interview process and how “New Mainers” have influenced her since. –Deb Dawson

DD – When Jan Pieter approached you with the concept of writing a book about Maine’s immigrant (restaurant) community, what inspired you to take on the project?

PN – When Jan Pieter approached me about writing the book, I agreed on the spot. As a journalist, I had noticed growing numbers of immigrants and was curious about them. I knew no one else had done a Maine book on the topic, so it had a good chance of publication. As a former Peace Corps volunteer in Afghanistan, I had mentored an Afghan family in Portland. And since my mother was a Dutch immigrant and I grew up surrounded by relatives from Holland, I had an affinity for people from other cultures.

DD – As the concept evolved from focusing on immigrants who owned restaurants to the broader immigrant community, how did you find and decide who to interview?

PN – Being thoroughly acquainted with Jan Pieter’s wonderful photography, I knew his photos would carry the book. Our collaboration was based on friendship and a mutual professional respect. We began our interviews + photos with immigrants we were aware of, but benefited thereafter from many identified for us by Reza Jalali, allowing us to reach our goal of 25 subjects/portraits. We aimed for diversity, including mostly but not only refugees, but also economic immigrants and a few others who found opportunity in Maine.

DD – Each subject had a very different history and experience to share, yet each profile feels very cohesive from one to the next. Can you describe your interview process and how you were able to tie them all together?

PN – Every subject in our book has a different story, yet as I interviewed them, I found themes emerging among the refugees: suffering and trauma in their home country, then rescue and hope, followed by a new set of challenges in Maine sometimes causing more suffering. As an interviewer, I tried to get to the essence of what their experience had been in their home country and since, and to elicit from them what was hard about living in Maine. The answers were unsurprising: a mix of welcome and intolerance from the local community. Maine was just getting used to people from faraway countries, people of color and different religions.

We chose not to expand on such themes, but rather let the subjects speak for themselves. I believe that is the reason for the success of our book: the portraits by Jan Pieter + immigrants in their own words as reported by me the best I could: hopefully the book offers an immediate interaction with the immigrant, photo + text, each and every one.

DD – The title, New Mainer has a very welcoming, inclusive connotation and has been adopted as an alternative title for those immigrating to Maine. Do you think this book has had a positive influence on our acceptance of “those from away”?

PN – The title “New Mainer” was thought up one night in Pownal at Jan Pieter’s kitchen table by him and me, or me and him, or it didn’t matter: it just happened. A special delight for me is that some recent immigrants now reject that label because . . . they’re not new any more, and they are political leaders. What better outcome for our book?

I like to think our book has had a positive influence on Mainers’ acceptance of “those from away,” but I don’t claim that. Many of our book sales are in educational settings, so that is good news. Beyond that, I hope that the swelling interest in this subject has had an effect. But I’m pessimistic that the others who are unaware of the wonderfully diversifying community in Maine participate. In today’s political climate, I’m always happy to see our book right there, in a bookstore, standing for tolerance. And that’s where I place my hopes for changing minds.

DD – How has the experience of this project influenced your writing since?

PN – Writing “New Mainers” has influenced my writing since then by reinforcing my commitment to helping refugees, which I do as advisor to Peace Corps Community for Refugees.com.

Morgain Bailey

Unsettled Geographies is the result of a year-long photographic project by lens-based artist Morgain Bailey.

Morgain Bailey, Watson Settlement Bridge, Maine 2020 - 2021, Inkjet print, 16 x 24 inches

Morgain Bailey, Dice, Van Buren, Maine 2020 - 2021, Inkjet print, 16 x 24 inches

Northeastern Maine has a rigid formalism in its appearance. Contrasting large-scale, semi-automated industrial agriculture with small family farms and expansive tree farms with pockets of protected wild lands, this area has a complexity that belies its initial appearance of catastrophically rigid sameness. This collection of photographs speaks to Morgain’s personal experience of this place over the course of a year and to the evolving meaning of photography in a time of rapid social and environmental change. The relevance of how we perceive new and unknown-to-us landscapes will become increasingly important as ever greater numbers of people migrate in response to climate change and in search of economic stability.

The inspiration for this work began with her migration to the northeastern corner of the United States, which is Aroostook County, Maine. Her migration was the result of a lifelong search for affordable housing and a response to climate change which included a desire to experience a longer winter. She found herself surrounded to the west, north and east by the United States-Canadian border and to the south by hundreds of miles of forest and very tiny towns. Curious about the closed geopolitical border, she began photo-documenting the border terrain, including the border posts and the uncrossable crossing stations. Then she moved inward and noticed repetition in the landscape. She was drawn to the architecture, colors, memorials, horizons, cultural debris, parked cars and the natural shapes found in the landscape, all of which became part of her image collection.

Morgain’s work is inspired by a complex process of integrating research into a creative practice based on experiencing the personality of place. Photographing this place without the knowledge of the region which its people have formed over millennia, she built the series of observations which form the body of this work. The project is about not having and not knowing. Not having knowledge or understanding of a place and not having an internal map made from the memories, emotional connections and accumulated knowledge which individuals develop and inherit from communities. It is about learning to understand a place when you just happen to be there. The covid-19 pandemic and its resulting isolation and loneliness are underlying themes of this work. Observing the geography of this unique place allowed Morgain to slowly gain insights into the personality of this rarely looked at part of the world and to connect with the terrain.

Interview with John Eide

by Jan Pieter van Voorst van Beest

John Eide created the photography program at Maine College of Art where he taught from 1970 to 2008. His work has been exhibited throughout the United States and is in the collections of the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Portland Museum of Art, the Library of Congress as well as a number of private collections. After taking a photography course from John in the 1970’s, Jan Pieter recently caught up with him for an interview.

Jan Pieter: When you came to Portland in 1970 and started the photography department at the Portland School of Art, what did you find in Maine as far as the photographic landscape? Was it difficult to get photography accepted as an art form here in Maine? What were the challenges in setting up a new photography department?

John: Portland and Maine were so different in 1970 than today, in all ways. In the late 1960’s John McKee started teaching one or two photography classes at Bowdoin. In 1969 Nick Dean started teaching a few classes at the Art School, now the Maine College of Art and Design. In 1971 Bill Collins asked me to create a four year BFA program in photography. In 1970, there were only two museums in the U.S. collecting photos; one commercial photo gallery. A few photo galleries connected to academic institutions.

All that exploded in the early seventies with every art department creating a photo program, museums starting collections and commercial galleries opening. Huge changes in ten years. But in 1980 you still could not get a good meal in Portland after nine pm. No gallery in Maine would show photos. I was showing my work in Boston quite frequently since it had a vibrant photo community. The Portland Museum saw the future and allowed me to curate three photo shows in the mid ‘70’s. There were only a handful of serious photographers living and working in Maine when I arrived. A few others would come up during the summers. I’d run into them in Boston. I really had no serious problems setting up a new program. Photography was a hot medium in the ‘70’s so students flocked to my classes.

John Eide, Freeport, 1972, Made with 35mm rangefinder camera, Silver gelatin print, 13 x 18 inches

Jan Pieter: When sequencing your work, making books is a natural road to take. You have done this with your Prague photographs, the Arizona series as well as with the granite series and other series of photographs. Having been a photographer for a long time do you ever discover a narrative in your work that starts in your early work and continues through present time and that you might want to sequence and put in book form or exhibition form? Do you use older work in new projects?

John: The quick and easy answers are: Yes, but No, and No. I have no desire to do a book sequencing my old work. I don’t want to go back to the old stuff. Nor do I have the desire to create a “retrospective” exhibition.

My way of working was simply to put film in the camera and go out. When time came for an exhibition, I’d look at the recent contact sheets and work prints to see what “fell into place”. There were always images on the contact sheets “leftover” from last time, and other images that just did not make sense. Yet, these images, the ones that did not make sense, were showing the way for “next time”.

John Eide, Arizona, 1992, Made with 35mm rangefinder camera, Silver gelatin print, 13 x 18 inches

Jan Pieter: Looking back over the years and the work you produced, what do you feel has been the major theme in your work and vision?

John: If there is a unifying element in my work it is the marks we make or traces we leave on our surroundings, whether it is graffiti on buildings or holes left on islands or buildings erected or initials carved in tree bark or melting icebergs. This thread can be traced back to my grad school work.

John Eide, Deering Oaks, 1978, Made with 4x5 view camera, Silver gelatin print, 4 x 5 inches

Jan Pieter: In your recent zoom cast, you made the statement that giving photographs titles limits the viewer’s response to the work. In recent art education curriculums I see a lot of attention is paid to the writing of the Artist Statement. Do you think that the same issue that exists with titles would count for Artists Statements as well? Quite often it seems that artist statements try to explain the work. Should good work not speak for itself?

John: Titles and an artist statement are two different issues.

I don’t title anything, other than the location and the date, because I want the image to trigger a response unique to that viewer at that time, without any direction from me. I would tell my students that if they focused all their life’s experience on the making of that image, it was the viewers responsibility to focus all of their life’s experience on reading that photograph. Not unlike two pyramids….., aiming all their energy at one photo. (I think I stole that idea from Minor White) .

I don’t think I’ve ever placed an artist statement on the wall. But, writing down our thoughts about our own work is important in understanding where we and the work are coming from. We’re visual people. Writing helps us hone our understanding of our own work. For this reason, I’d often ask my students to write about their work. And also to write about their colleague’s work.

John Eide, Paris, 1983, Made with 35mm rangefinder camera, Silver gelatin print, 13 x 18 inches

Jan Pieter: Photography, probably being the art form that is mostly influenced by changing technology, has been in constant flux. I see a lot of mixed media art these days that include photography in the mix as well. There are even curators that talk about photo based art rather than talking about photography. What in your opinion drives these changes: the art critics, curators and educators, technology, or the choices of talented artists? What direction do you see photography going?

John: Each one of these sentences is the topic for a PhD thesis or a graduate seminar. Technology changes or new technology is created, because our society/ culture demands those changes or those new processes for one reason or another. Sometimes artists take a newly created technology in an unexpected direction.

John Eide, Minneapolis, 1968, Made with 4x5 view camera, Silver gelatin print, 4 x 5 inches

Jan Pieter: Having had a close relationship with the sea my whole life myself and knowing that you have been a sailor as well as a photographer for a long time, have the two (photography and sailing) influenced each other and your work?

John: To a degree.

I could never have done Traces on the Hardway had I not been sailing the coast of Maine and seen the remnants of the quarry industry. Only a few of the islands I photographed are accessible by public ferry. The rest are private islands and only accessible by small boat. There is a small body of work made while sailing solo on an earlier and smaller boat. I scared the hell out of myself the following winter when printing these images because I realized I could easily have fallen overboard while concentrating on making the photo and not on concentrating on sailing the boat. I never followed through on that work, for my own safety. Sailing introduced me to a fellow sailor, now a good friend, which resulted in the invitation to sail down the Antarctic Peninsula. Only serious experienced sailors were invited. No duffers. Then there is the quality of light and color and atmosphere that I’ve only experienced well offshore. Nowhere else. One should never take FEAR on a boat. Which is the same with strapping a camera to your wrist and wading into whatever it is you want to photograph. That said, there was a street in Paris, another in Tunis, a square in Montenegro where one look told me to turn around and find a nice café.

John Eide, Near Cape Horn, 2014, Made with DSLR camera, Inkjet print, 13 x 18 inches

Jan Pieter: You stated that the two major tools you have used in your photographic career are the 4x5 view camera and the Leica. Yet, looking at some of the work that you did with the view camera and by putting a pretty wide lens on it, I feel that it has a spontaneous 35 mm feel to it (Arizona work). What are your main considerations for choosing a certain format camera when planning a project?

John: Using a large format camera is more of a meditative process than using a 35mm camera. One works with the subject making adjustments until the image is as complete as one can make it. Then one sheet of film goes in and the shutter released. With a Leica, one moves more fluidly, releasing the shutter often many times as one works with the subject. More often than not, the last image is the keeper, the rest are sketches leading up to that one good one. Both are dances, but dances with different beats.

John Eide, Minneapolis, 1969, Made with 4x5 view camera, Silver gelatin print, 4 x 5 inches

John Eide, Paris, #3, 1983, Made with 35mm rangefinder camera, Silver gelatin print, 13 x 18 inches

“If we are looking for insurance against want and oppression, we will find it only in our neighbors' prosperity and goodwill and, beyond that, in the good health of our worldly places, our homelands. If we were sincerely looking for a place of safety, for real security and success, then we would begin to turn to our communities - and not the communities simply of our human neighbors but also of the water, earth, and air, the plants and animals, all the creatures with whom our local life is shared.” - Wendel Berry

My Place

by Amy E. Sklansky (1971- )

Universe

Galaxy

Solar System

Planet

Continent

Country

State

City

Me