My hope for these spring issues was that we would have a figurative focus that explores sexuality, gender, procreation in the nature, and the senses. It got away from us. So many other projects came to light.

If you have something wonderful and relative, send it here.

– Denise Froehlich, MMPA Director

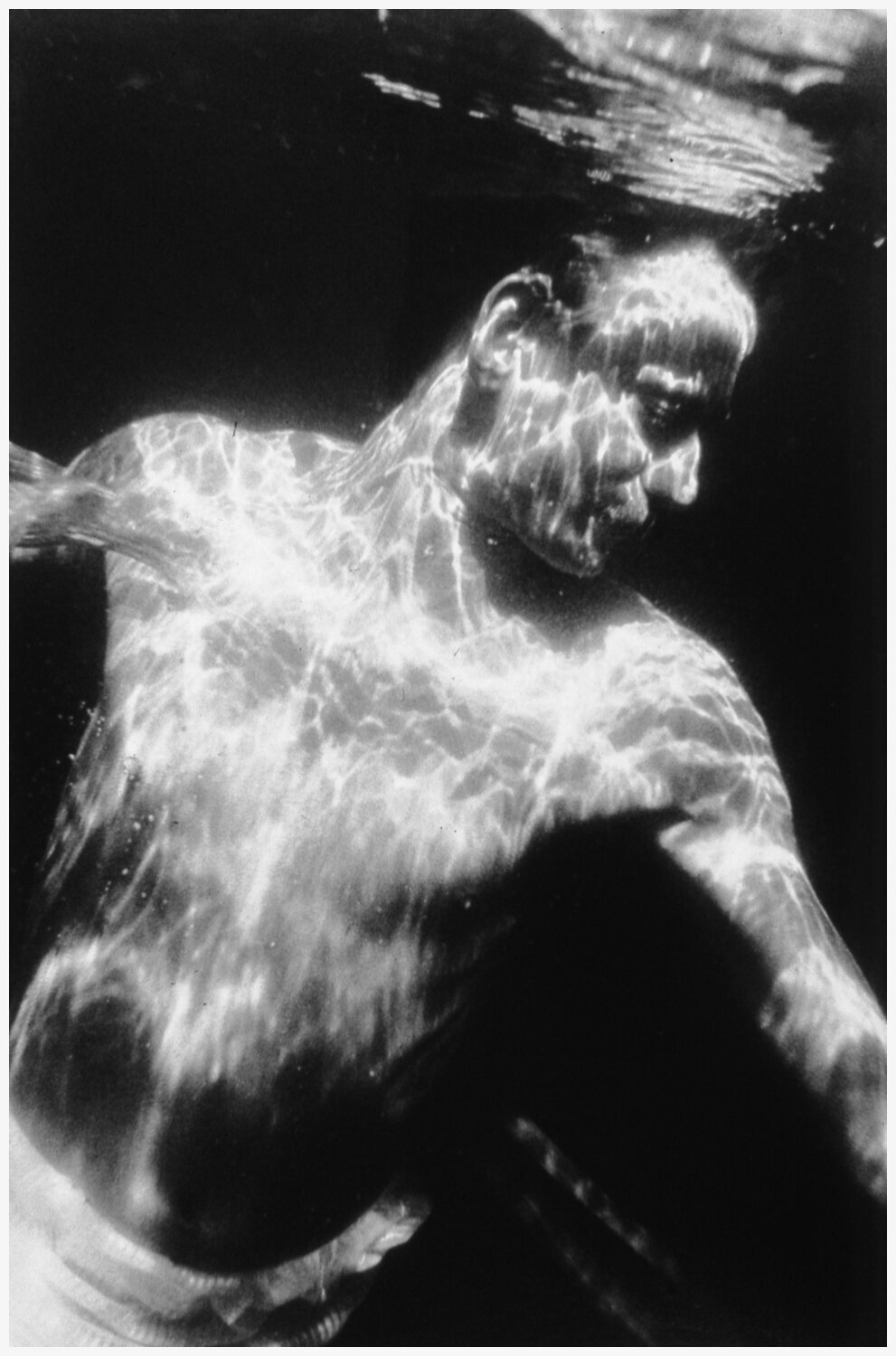

Jan Pieter remembers a portfolio by Nanci Kahn that reminded him of spring

Nanci Kahn is a photographer and sculptor based in Falmouth Maine. Currently she is also the Curator of Photography at the Maine Jewish Museum in Portland Maine. When I recently spoke to her I reminded her of the time, at least 15 or 20 years ago, when we both participated in a group exhibit of photography at the “Galeyrie” gallery in Falmouth Maine. Nanci showed some lovely underwater nude photography that got my attention. Thinking of spring and spring subjects for “Antidote” I asked Nanci if she’d like to show some of that imagery in our (Springtime) issue. I was not disappointed seeing these images again. It supports my theory that of all the photography and art we see, a lot of it is forgettable but the good stuff stays with you. These images did. JPvVvB

Deb Dawson Investigates Wilt Press on Peaks Island

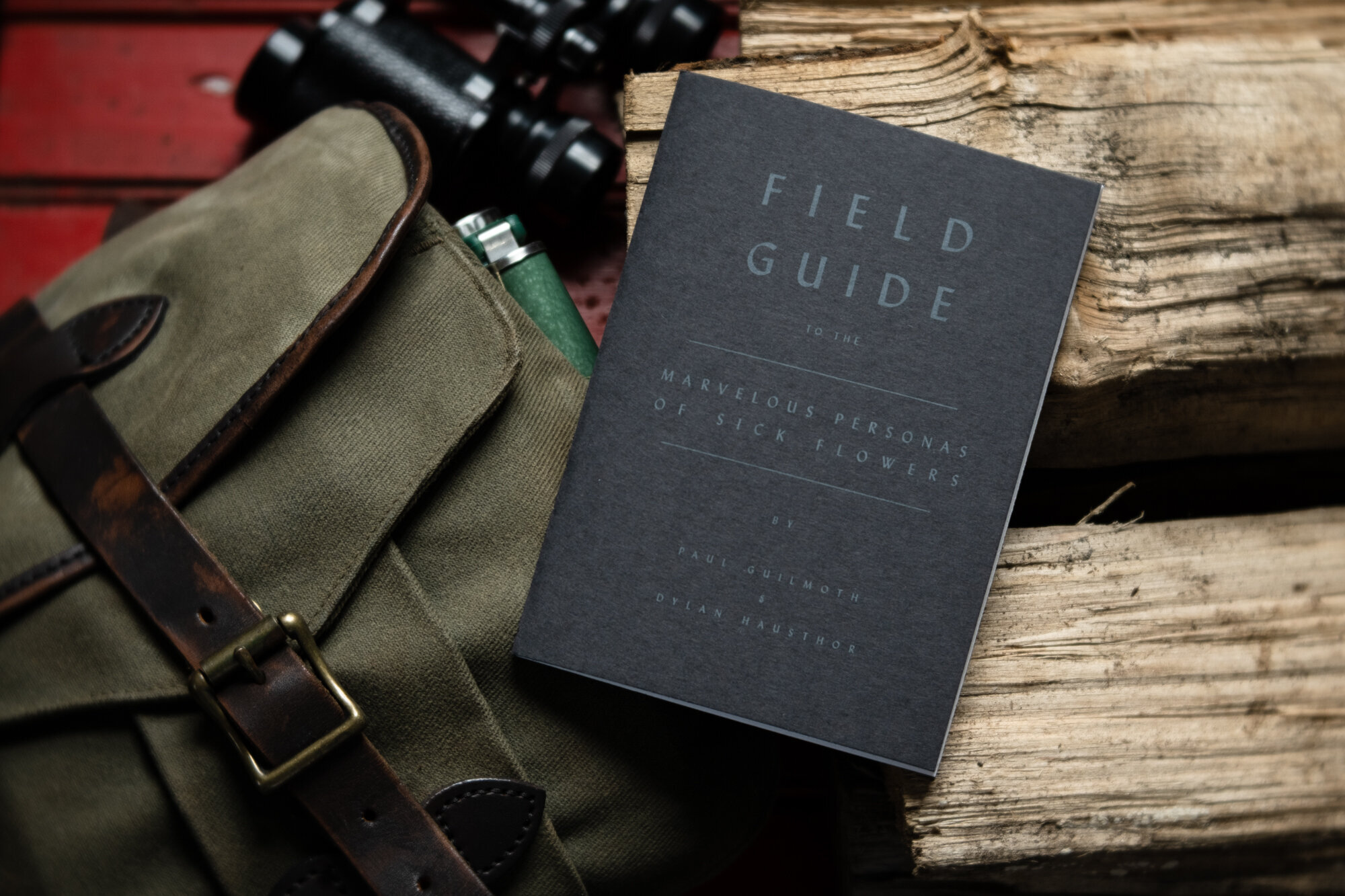

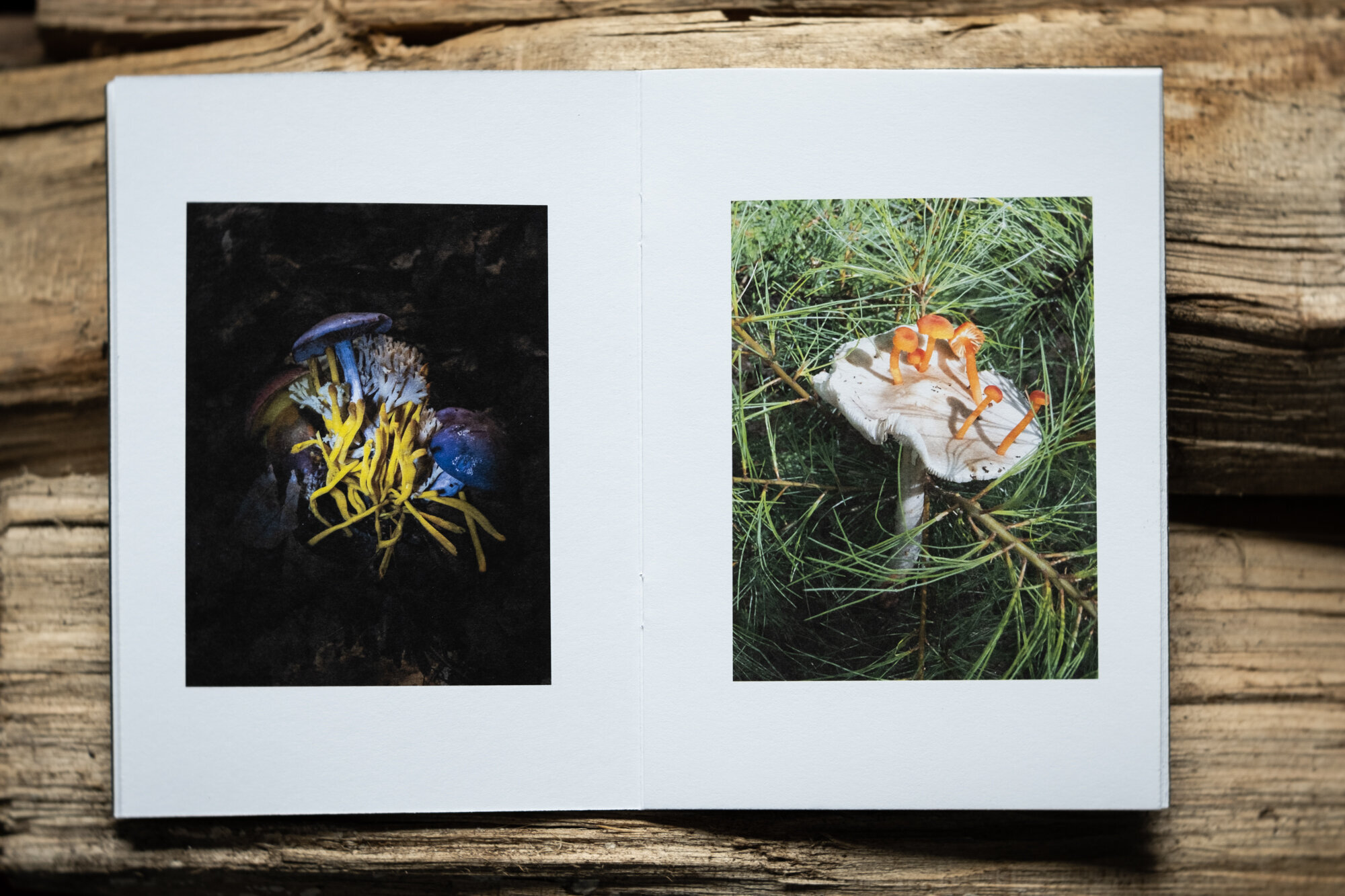

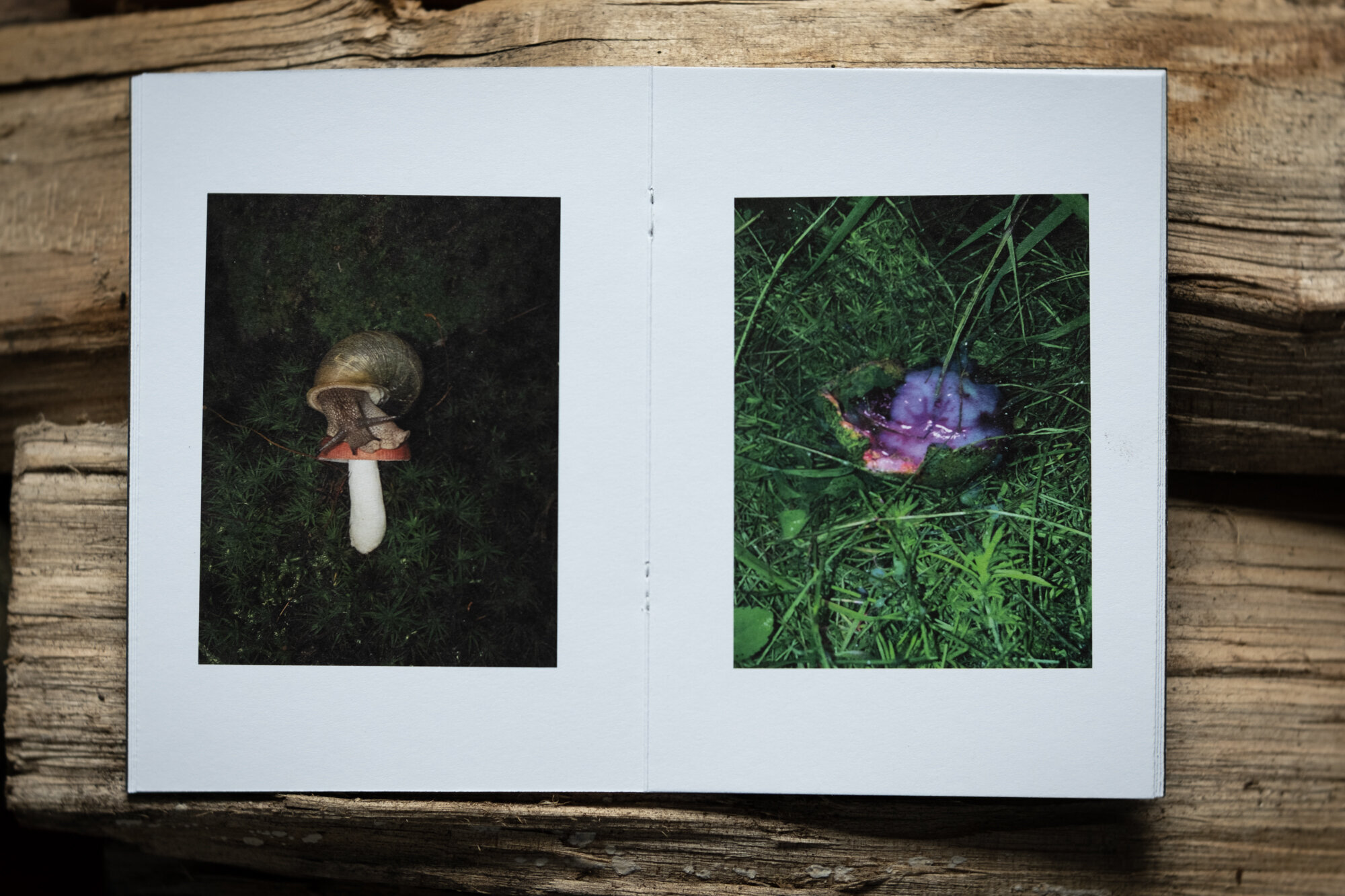

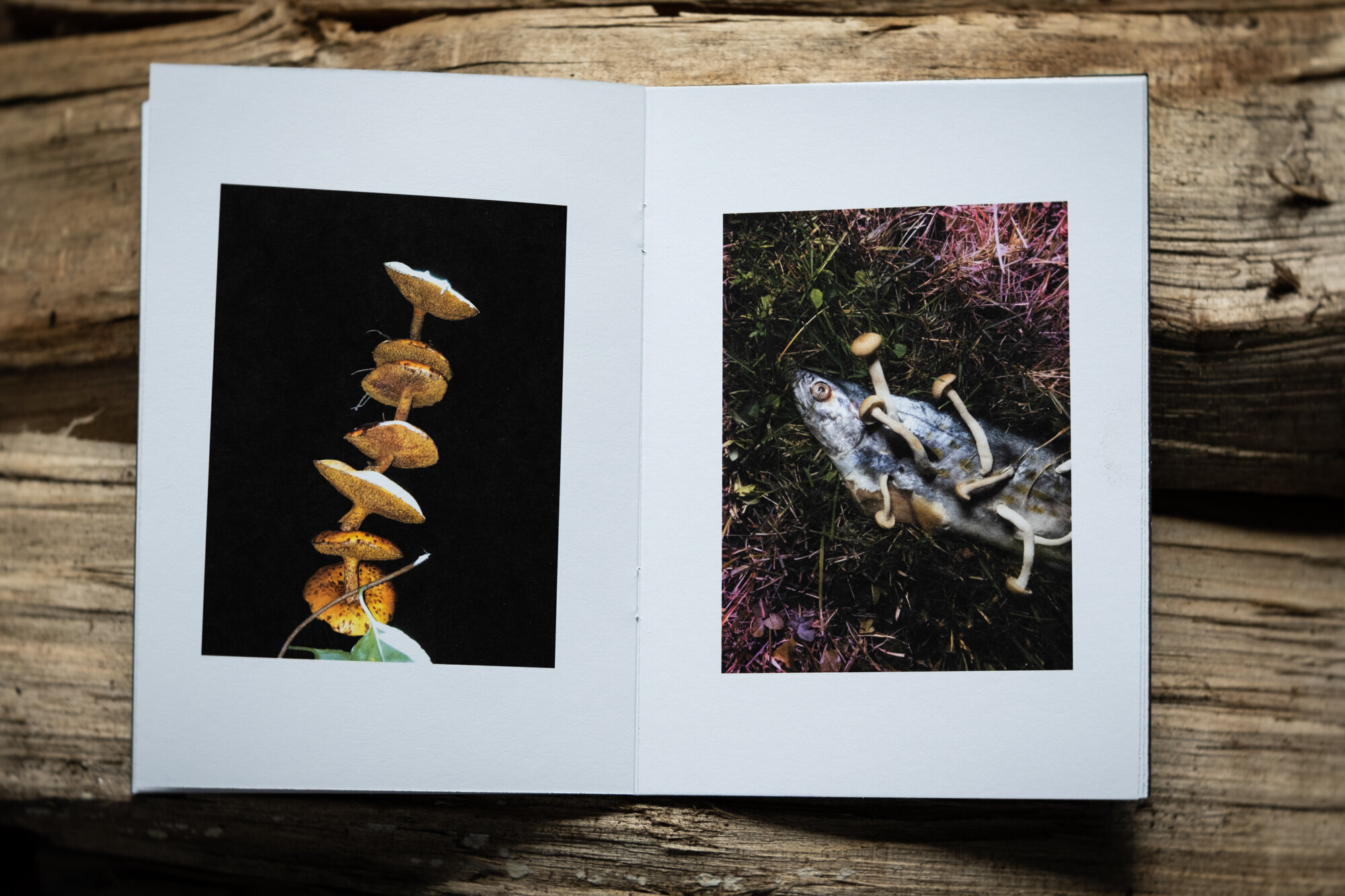

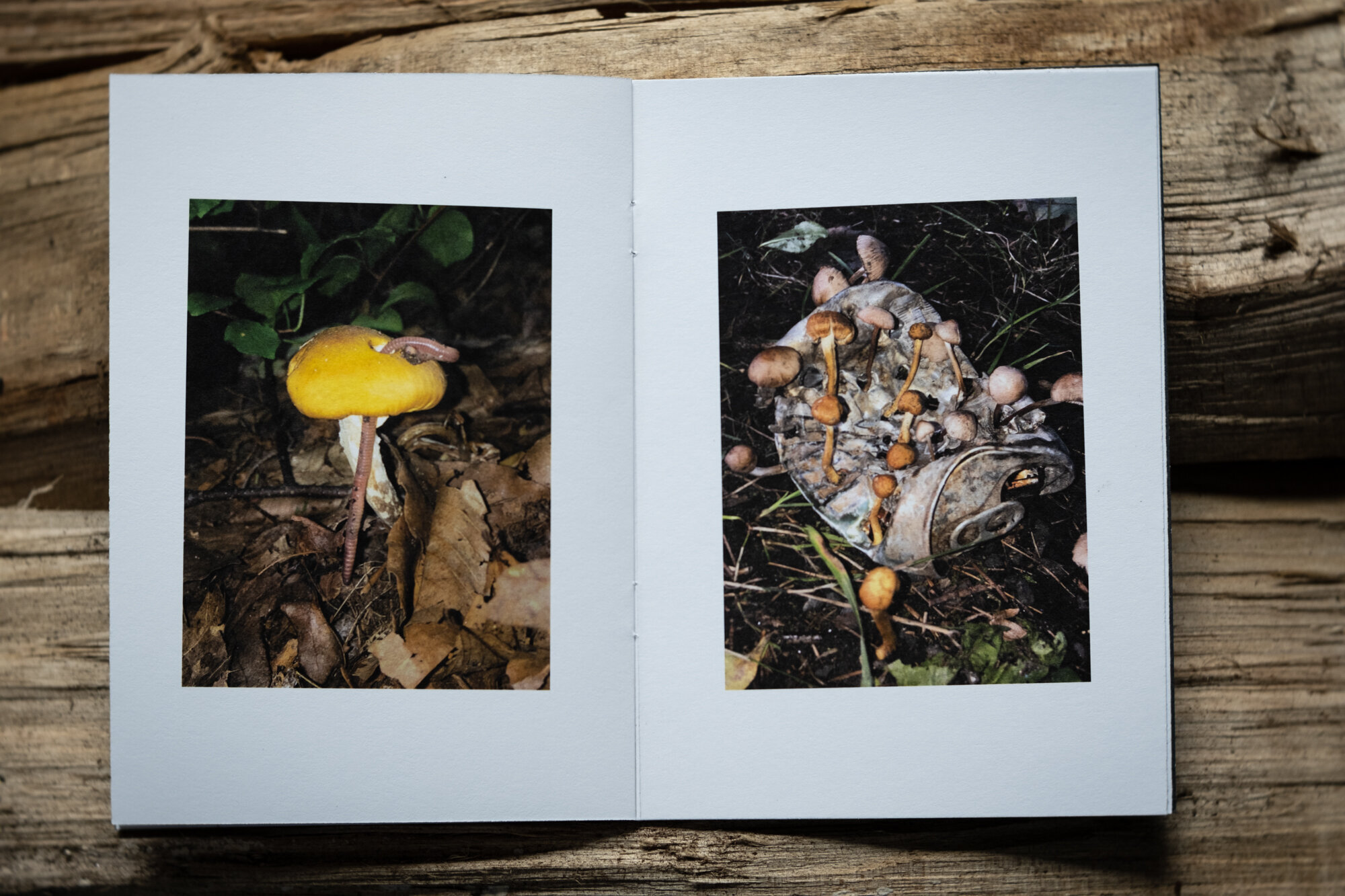

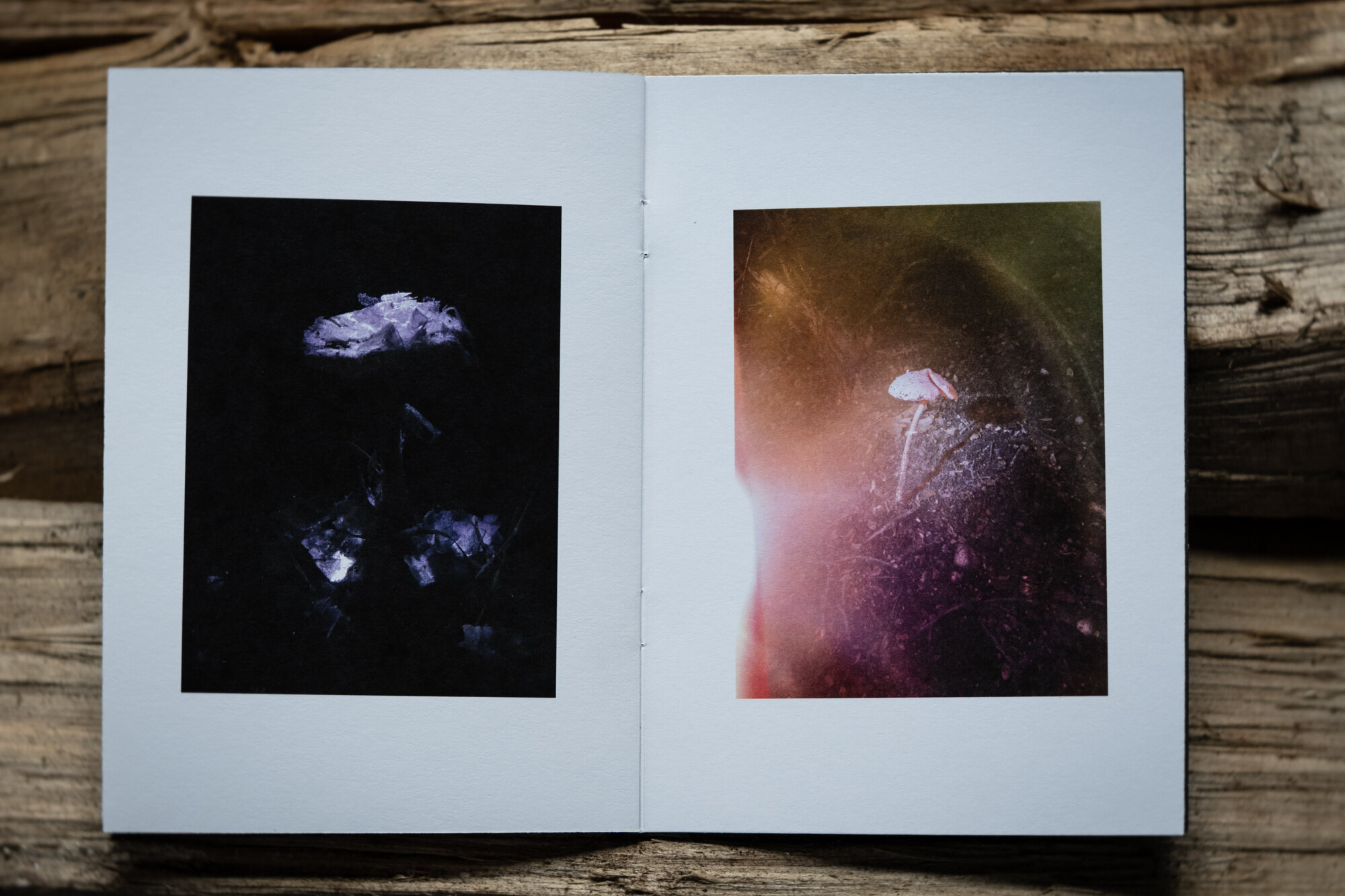

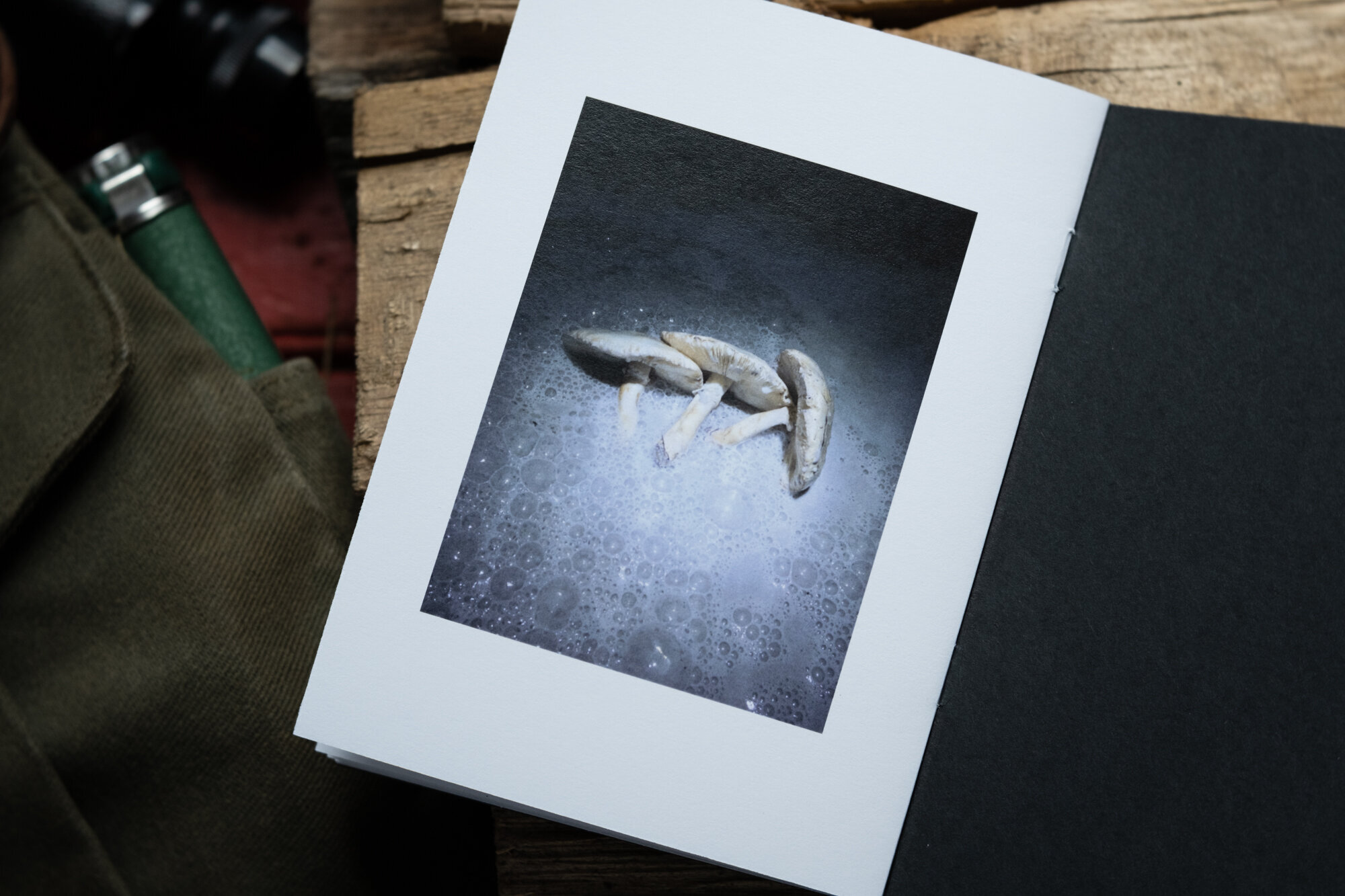

Opening the mailbox the other day I was greeted with an epiphany in a brown padded envelope with hand drawn art and crazy cool typography. It was almost too beautiful to rip open. I had to stand back and appreciate the hand that tended to its creation. Inside was an amazing collection of contemporary poetry and photography from my neighbors over on Peaks Island, Dylan Hausthor and Paul Guilmoth. Together, they run Wilt Press – an art book, music label, and very prolific publisher of Wilt magazine, cassette tapes and various forms of printed ephemera.

As I poured over edition 2 of Wilt Magazine and the other hand crafted small art books and zines I realized what I’ve been missing during this year of Zoom classes and online exhibitions. What I’ve been craving lately is real, tangible art—something where I can see the chunks of paint strokes on a canvas or hold a handmade book in my own hands. The package from Dylan and Paul at Wilt Press that greeted me in the mailbox was a great reminder of the art that makes us human. Proceeds from Wilt Press sales go to mutual aid organizations to help dismantle systemic racism, capitalism, the gender binary and queer hate. I can’t think of a better way to support our fellow human beings. Check them out http://www.wilt.press/ DD

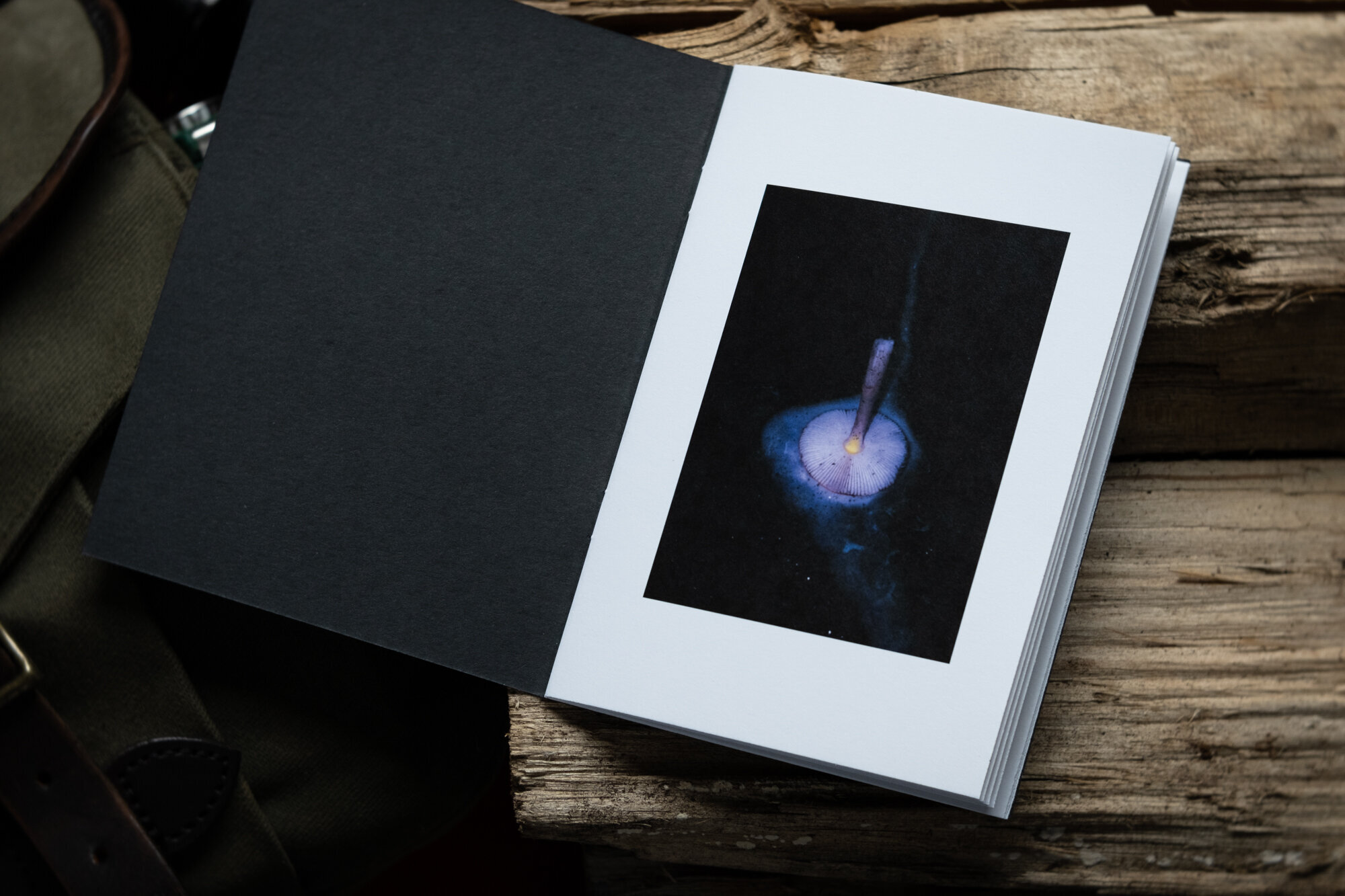

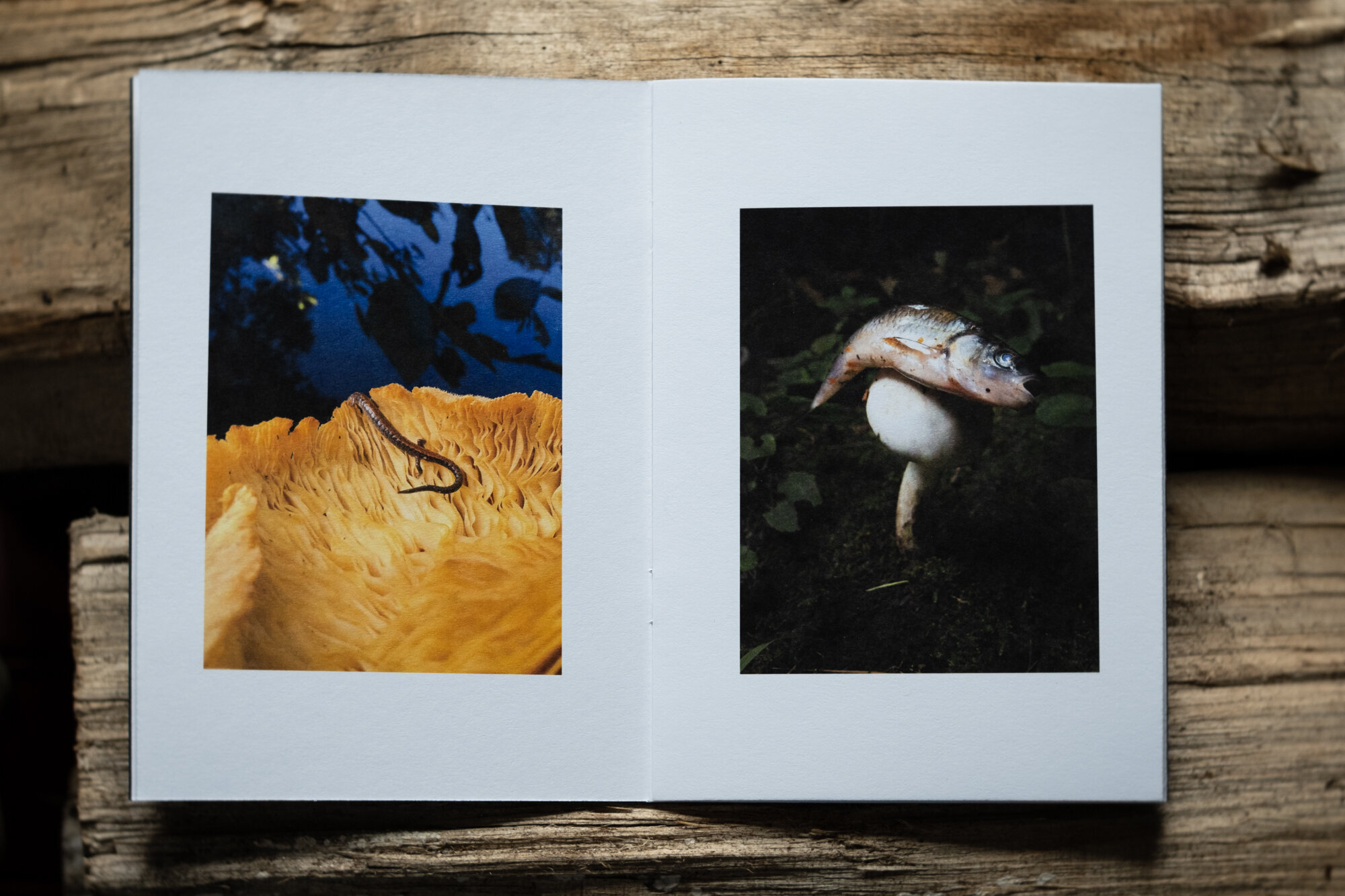

In the spirit of Spring I thought I’d share the Field Guide to the Marvelous Personas of Sick Flowers by Paul Guilmoth and Dylan Hausthor. It’s like exploring the deep misty woods with a flashlight and camera to illuminate another world of mystery at your feet. DD

Cemetery

by Bill Shumaker

Bill Shumaker, Cemetry, 2020, 50 pages, 8 x 10 inches available at AurelianImagery.com

Cemeteries offer us emotional respite as a quiet physical space and also as a place that encourages the visitor to keep life’s troubles in perspective. And yet these are spaces saturated with emotion – there is so much loss gathered in one place. As we look around them cemeteries confront us with the irony of memory. At the death of a loved one, memory struggles to overcome loss. Later someone commissions for the grave a headstone that meets the family’s aesthetic standards. Memorials placed prior to the bland uniformity of stones from about 1930 onwards form a fascinating museum of popularly selected art. But consider the recurring theme: “In memoriam ...”, “In loving memory of ...”, “Sacred to the memory of ...”. The monuments seem intended to stand as something that will outlast the memories of living persons, and they do, but to what purpose? While we can honor the dead for the examples of their lives, still as descendants and strangers we cannot truly remember most of them, despite what their stones say. This irony appears most poignantly on fallen and shattered stones; clearly no one now remembers, or cares. First the persons themselves are lost, then all memories of them are lost as well.

As time wars against memory, so nature wars against the artificial order of the cemetery. In cold climates the frost heaves at the upright markers in their orderly rows, tilting them to crazy angles and ultimately dumping them over entirely. Blue-gray and fiery orange lichens flourish on the carved surfaces; rain softens inscriptions until they can no longer be deciphered. Ultimately it is nature, not love or memory, that conquers all.

My cemetery photographs are intended as a meditation on mortality, loss, the universality of mourning, and the eternal desire of humans to overcome these through the creation of monuments and artwork dedicated to those who have passed on. BS

POETRY CURATED BY WILLIAM AND ANGELA MALONEY

Book collectors (15,000ish) and farmers, they own Late Light Farm in Acton, Maine

”I don’t like the word poetry, and I don’t like poetry readings, and I usually don’t like poets. I would much prefer describing myself and what I do as: I’m a kind of curator, and I’m kind of a night-owl reporter

– Tom Waits

In the spring, at the end of the day, you should smell like dirt.

– Margaret Atwood

We are our own photographers

by Vincent Pozon

We take fewer pictures of sunsets now,

fewer of gnarled branches and mountain ranges,

we looked at the camera and told it

to face us.

It has not stopped taking our pictures since,

at every turn and corner of our slow lives,

at every hump and groan of our fast roads,

we smile, or do not.

It is ear-to-ear or demure, we wear sardonic,

or crook a brow, chests heavy, with hope or hurt,

we stretch that arm when we love and feign love,

we take a selfie.

We include every silly soul behind us,

in parties, at work, when we wade into wakes.

We stretch our arms, insinuate ourselves

into snapshots of sunsets.

Our lives sear onto a form better than paper,

fixed and unflinching, events cannot be changed

by how others may remember them,

or by our faithlessness.

We record, not for the curious among

our kith and kin, we are photographers

of our own photographs, fleshing out

our personae.

We document the dull business of the day,

and the squandering of the nighttime,

our decline and decay, our bloating,

our greying.

Historians are euphoric, we are the generation

most documented, we were here, indubitably,

we all have diaries, they're on the internet,

floating forever.