The Mind of Winter

The Snowman

by Wallace Stevens ( 1879-1955)

One must have a mind of winter

To regard the frost and the boughs

Of the pine-trees crusted with snow;

And have been cold a long time

To behold the junipers shagged with ice,

The spruces rough in the distant glitter

Of the January sun; and not to think

Of any misery in the sound of the wind,

In the sound of a few leaves,

Which is the sound of the land

Full of the same wind

That is blowing in the same bare place

For the listener, who listens in the snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.

CAROL EISENBERG FROM HER UNDERCURRENTS PORTFOLIO

Carol Eisenberg, Blue water, 2021, Photo based digital constructions, Inkjet print, 45 x 60 inches

Hunting Ghosts with Dylan Hausthor

In the 2021 Spring Issue of Antidote we featured Wilt Press, the collaborative work of Dylan Hausthor and Paul Guilmoth of Peaks Island. Dylan Hausthor recently completed their MFA at Yale University and is about to embark on an artist residency at the Ellis-Beauregard Foundation. Given my brief preview of Dylan’s work, I can’t wait to see what comes next. Until then, Dylan is teaching a workshop at Maine Media Workshops + College, “The Storyteller and the Specter”. February 3 through March 10. This could be a brief window into that mysterious, liminal space between documentary, storytelling and the past that haunts us.

- Deb Dawson

Here’s the MMW+C Course Description:

Images have a longstanding relationship with storytelling. When we tell stories, how do our pasts haunt us? How does the land where we make our work seep into the images’ content? Where does fact become fiction? When does history become lore? How does memory become truth? In this course, we will discuss what it means to indulge the tradition of storytelling through ritual and imagery. We will hunt for ghosts, both literally and metaphorically, and interrogate the traditions that allow those ghosts to haunt us. As image-makers, our role and responsibilities to the stories we tell continue to shape shift, and the way in which lore becomes infinitely important. We will begin exploring the non-border between facts and fiction, the role of identity, what it means to haunt, and how (or if) histories of the occult can inform these practices. Dylan’s work, reflects an elemental experience of living close to the land while exploring the mysteries of their island community. They offer this insight into the latest work.

My name is dylan. I make photographs, videos, writing, and books. I think about myth making, disinformation, and animals. i praise at the altar of story. I work as a teacher and mushroom farmer. I live on an island in maine and like to wear camo t shirts even though I’ve never eaten meat. I spend most of my time in Maine, Oregon, and Massachusetts.

What the Rain Might Bring is about small-town gossip, relationships to the land, the mysteries of wildlife, the drama of humanity, and the unpredictability of human spectacle inspire the stories in this work. I’m fascinated by the instability of storytelling and hope to enable character and landscape to act as gossip in their own right: cross-pollinating and synthesizing.

The often disregarded underbelly of a post-fact world seems to be the simultaneous beauty and danger of fiction. I’m interested in photography and bookmaking as mediums of hybridity—weavings of myth filled with tangents and nuances, treading the lines between investigative journalism, performance, acts of obsession, and self-conscious manipulation. I’m interested in pushing past questions of validity that form the base tradition of colonialism in storytelling and folklore and into a much more human sense of reality: faulted, broken, and real. - DH

These people have given Generously to MMPA this season.

Thank you!

Ella and Knapp Hudson

Jack Montgomery

Jeff and Hillary Becton

Peter and Pam Plumb

The Portland Camera Club

Richard and Jeanne Press

Bill Press

Ralph SeGall

Harry Brandler

Judy E. Glickman Lauder

Joel R. Ferris

Steve Fielding

Donna Katsiaficas

Ann Fisher

Cindy Mervis

Fred Nene

William Gilliss

David Little

Karen Olson

Steven Keirstead

Jack Montgomery

Photogravure Overview

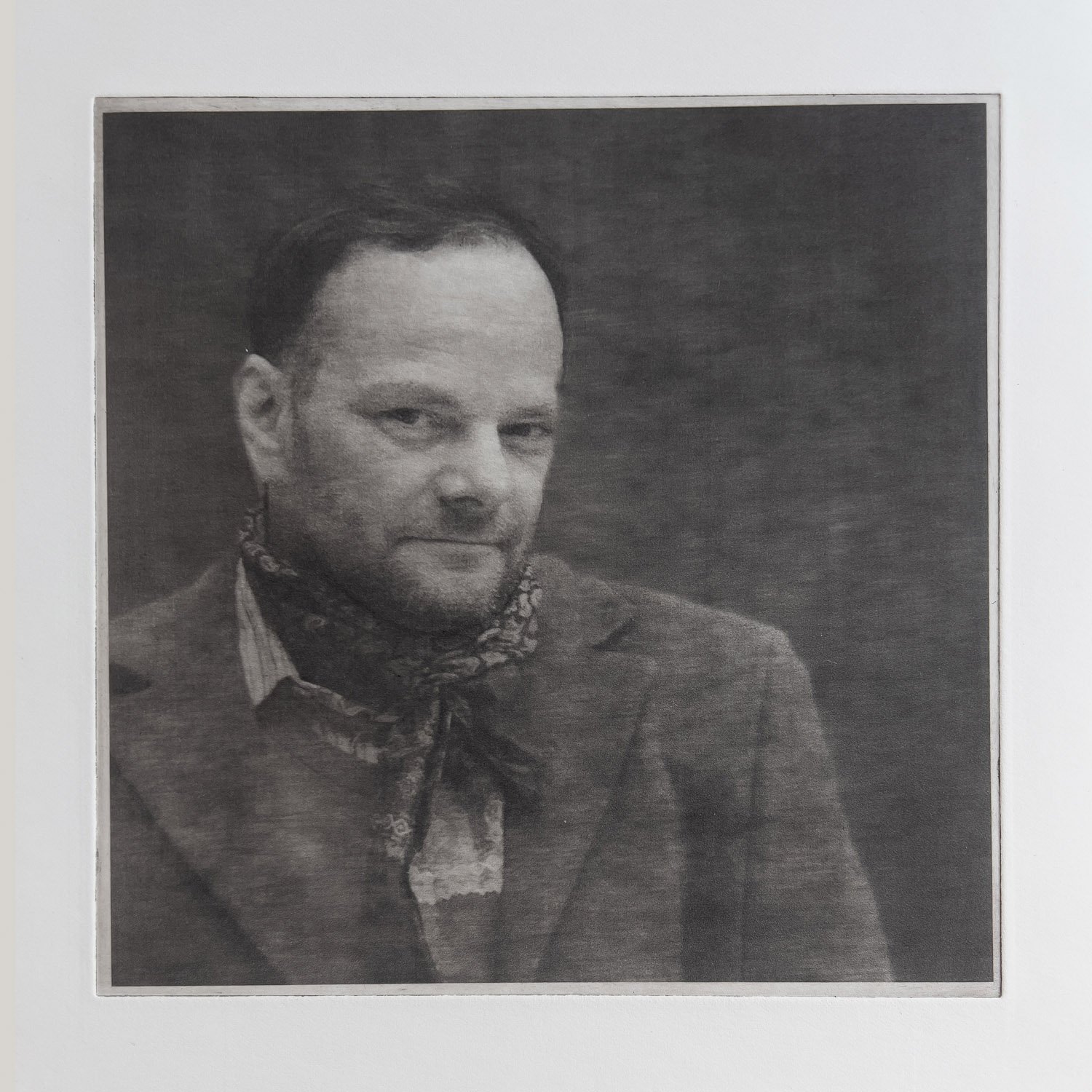

Jack Montgomery, Friends, Berlin, Germany, 2021, Photogravure, 7.5 x 7.5 inches

Photogravure is a process invented in the 19th Century by which a two dimensional photograph is transmuted into a three dimensional etching plate. The images become a series of grooves and indentations on a metal plate that is then covered with ink, wiped clean except for the ink remaining in the grooves, and then run through an etching press with damp paper lying on top of the plate. If successful, the image is transferred onto the paper. This is an intaglio process, essentially identical to that employed by Durer and Rembrandt centuries ago, although those earlier artists scratched their images onto a wax covered plate with a stylus (burin). Alfred Stieglitz was one of the early masters of photogravure and used the process in the printing of his seminal magazine, Camera Work. The earlier processes involved harsh and potentially dangerous chemicals. More recently, polymer plates, developed in water rather than acids, permit a more benign workflow.

Since I began photographing seriously in the early 1990’s, I have been moved by the Photo Secessionists (early Edward Steichen, F. Holland Day, Clarence White) as well as the French photographer, Robert Demachy. I am a shameless romantic. I have tried several alternative processes through the years but it was photogravure that captured my greatest interest. In late 2019 I attended a local art sale and was captivated by etchings done by Andrea van Voorst van Beest. There is something about ink on paper that really excites me. I would turn 70 in a month. So I decided it was time to take the plunge (“if not now, when?”), purchase an etching press and learn how to make the photogravures. I bought my first press (a used Dick Blick 906) for $300 off Facebook Marketplace in December 2019 and then drove up to the Presque Isle area for a three day intensive course with a wonderful Maine artist, printer and poet, Jeanne Wells. I was hooked.

In January 2020 I was making progress and decided to jump in with both feet. I ordered a serious table top press manufactured by Takach. And then Covid happened. I think my press was one of the last to leave the factory before it shut down. It arrived on a pallet, dropped in our garage on a sunny winter day. Because my wife and I were isolating completely, our first challenge was to get this 350 pound monster into my studio. The solution was to disassemble it and carry the pieces through the yard in our Garden Way cart. Once reassembled, it was ready to go. The timing could not have been better. Throughout the pandemic, one of my greatest pleasures has been the slow process of making photogravure images. There is a ritual to all this and it requires great concentration. I find it very peaceful.

—JM

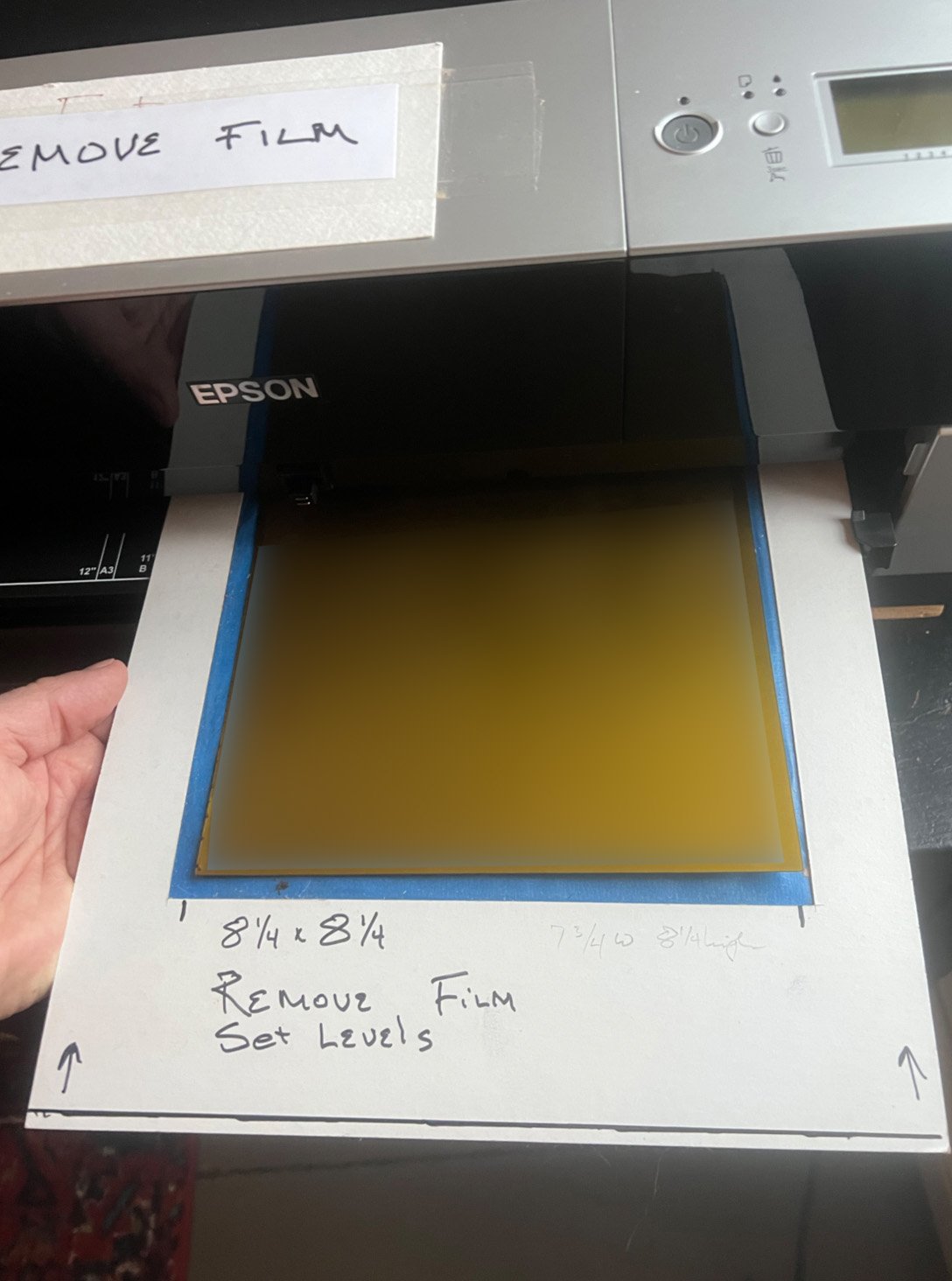

The Direct to Plate, Polymer Photogravure Process

First Step

Preparing the Image: An image is selected. It can be in any format but must be digitized. Many of my images are scans from 2 1/4 negatives shot with my Hasselblad. Some are from my iPhone or my Ricoh GR pocket camera. For this discussion I will be focusing on a portrait I made in Berlin in 2017 with the Ricoh — my friends El Fox and Alexandra. Here is the image right out of the camera: The buildings behind are a reflection in the glass, not a multiple exposure.

The image is then converted to black and white.

The next step is one of the most challenging aspects of photogravure. The image must be processed in a manner that will give a full tonal range and continuous tones when processed on the etching plate. I was fortunate to study (on Zoom) with an Australian photographer/ printmaker, Silvi Glattauer, who taught me a relatively simple method that I have used ever since. Here is what the image looks like cropped, reversed and processed, ready to print on the polymer etching plate.

Second Step - Making the Plate

The prepared image is printed on a blank polymer plate. These plates are available from a number of sources and are also used in the commercial printing world. There are a number of types though the pandemic has made some varieties very scarce. I print my plates on an Epson 3880, using the manual front loading process with the plate nested in a matte board carrier.

The plate, now bearing the image printed on its surface, is placed in a UV box and exposed for 90 seconds. (These exposure times vary according to the type of UV box, the type of polymer plate and other factors. 90 seconds is optimum for my workflow.)

After exposure, the plate is placed in a water bath (about 68 degrees F) and gently washed with a soft sponge. This removes the ink and excess polymer that was not hardened by the UV light. The plate is then dried, heated and returned to the UV box for another 10 minutes of exposure to fully harden the polymer. At the end of this process the images can be seen on the face of the plate when held in a cross light.

Third Step: Inking the Plate.

The hardened plate is next placed on the inking bench and covered with a thin layer of ink. There are many types and colors of ink available. I prefer Aquarelle water based inks but purists insist on oil base inks which are much more difficult to clean. There are also many ways to apply the ink. The brayer works best for me.

After the plate is fully inked, it is then wiped with a cloth. The purpose of the wiping is to remove most of the ink from the areas that will appear lightest in the print while allowing the ink in the deeper grooves to remain and thus print darker. Again, there are many cloth choices. I have had good luck with the Akua cloth in combination with my ink choices. The wiping process is one of several points where creative choices must be made — how hard to wipe, what temperature, use of hands for wiping and many more.

Once the plate is wiped, it is ready to print.

Fourth Step

Printing the Image While the plate is being prepared, water color paper is dampened. A small degree of dampness is essential to assure a transfer of the ink from the plate to the paper when run through the press. Again, there are many techniques for dampening. My choice is to leave it in a tray of fresh water for half an hour or more. I then place it between the folds of a towel to dry, running my hands over the surface of the outer towel fold. If the paper is too damp when printed it will adhere to the plate, ruining the print and requiring some serious effort to clean and re-ink the plate. Learning to judge the proper dampness took me awhile (with many ruined prints in the process).

The inked plate is now placed on the bed of the etching press.

The dampened water color paper is then placed over the plate and the felt blankets (seen on the right side of the image above) are then laid over the “sandwich” of plate and paper. The press is then cranked, forcing the sandwich between two large rollers. The paper is thus pressed with hundreds of pounds of pressure, causing the ink to transfer from the plate to the paper.

The press bed emerges on the right side of the press, the paper is gently lifted from the plate, and the final image appears, clean and free of adhesions to the plate (hopefully!).

The print is then placed between two pieces of blank newsprint and placed between sheets of sheetrock for flattening and drying.

In summary, the process is slow and, for me, extremely satisfying. Nice music and a little wine doesn’t detract from the experience on a cold, snowy day. -JM

Jack Montgomery, Trees above the Lake, Viterbo, Italy, 2020, Photogravure, 7.5 x 11 inches

Jack Montgomery, Spear Farm Pond, Freeport, Maine, 2021, Photogravure, 7 x 11 inches

Jack Montgomery, Bartlett Street Rooms, Lewiston, 2021, Photogravure, 10 x 10 inches

Jack Montgomery, Alex, Paris, 2020, Photogravure, 7.5 x 7.5 inches

By any measure

by Ben Lerner (1979 - )

By any measure, it was endless

winter. Emulsions with

Then circled the lake like

This is it. This April will be

Inadequate sensitivity to green. I rose

early, erased for an hour

Silk-brush and ax

I'd like to think I'm a different person

latent image fading

around the edges and ears

Overall a tighter face

now. Is it so hard for you to understand

From the drop-down menu

In a cluster of eight poems, I selected

sleep, but could not

I decided to change everything

Composed entirely of stills

or fade into the trees

but could not

remember the dream

save for one brief shot

of a woman opening her eyes

Ari, pick up. I'm a different person

In a perfect world, this would be

April, or an associated concept

Green to the touch

several feet away

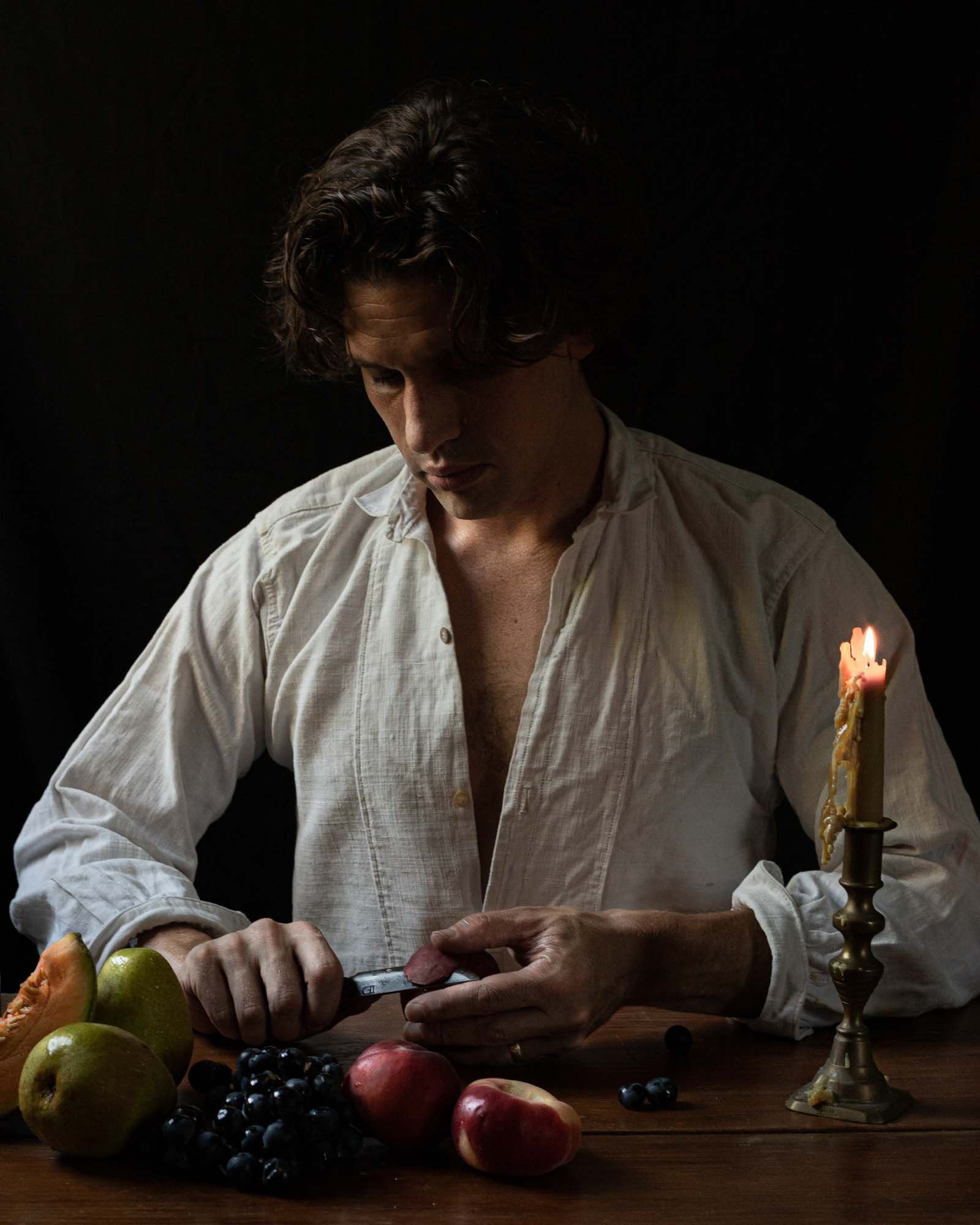

Ari Kellerman, Nature MortE

I began shooting still lives during the pandemic as a passion project. With most of my photography jobs on hold along with my work in museum education, I needed to find something to bring purpose to my days. The series began in lockdown when like everyone, I was only venturing to the local grocer for outside interaction. I watched the seasons change through the food and flowers that were available. I studied the selection, taking visual notes of petals, stems, shapes, and textures. This gave me some sort of connection to the local community and I found long lasting joy in developing my practice and searching for inspiration and props around my home. A friend, a pet, and my husband sat for me and I leaned into keeping it simple with what was right in front of me. - AK